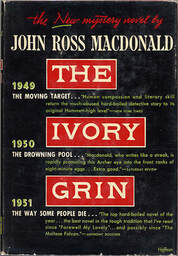

But what elevates The Ivory Grin from its pulp origins into a more literary arena is MacDonald’s no-nonsense observations and descriptions that provide a very believable snapshot of American race relations in the early 1950s. There’s no preaching here, and no didactic moral, just dozens of details: the casually dismissive sheriff of a young black woman’s murder; Archer’s belief (via evidence and logic) that Lucy’s boyfriend Alex did not kill her, even though he fled from the scene; client Una's initial accusation of theft, meant to be taken without question by the upper-class accuser; and the cold truth that Lucy’s death is ultimately insignificant to the cast of wealthy white people who have larger, class-rooted secrets to conceal. The story may have been written by a white man and might feature a white protagonist (and ultimately tell a white story), but Ross MacDonald is intensely interested in exploring this culture of double standards. If he wasn’t, he would not have bothered to deliver consistently illuminating descriptions in his prose. Take this sketch of a "beautiful" city divided by race and class:

The highway was a rough social equator bisecting the community into lighter and darker hemispheres. Above it in the northern hemisphere lived the whites who owned and operated the banks and churches, clothing and grocery and liquor stores. In the smaller section below it, cramped and broken up by ice plants, warehouses, laundries, lived the darker ones, the Mexicans and Negroes who did most of the manual work in Bella City and its hinterland.

Housewives black, brown, and sallow were hugging parcels and pushing shopping carts on the sidewalk. Above them a ramshackle house, with paired front windows like eyes demented by earthquake memories, advertised Rooms for Transients on one side, Palm Reading on the other. A couple of Mexican children, boy and girl, strolled hand in hand in a timeless noon on their way to an early marriage.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed