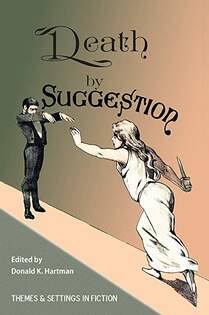

It turns out, hypnotism stories of vengeance, crime, and tragic outcomes became a cottage industry in the literary world of the 1880s through the 1910s. In Death by Suggestion, a new anthology from Themes & Settings in Fiction Press, editor Donald K. Hartman assembles an impressive collection of 22 tales from that era dealing with the theme.

One question I had before reading was whether the assembled stories, focused on so narrow a subject and following an anticipated narrative, would feel repetitive when collected and read in a group. The answer is Yes and No; there is some welcome variety in the use of hypnotism within the plots, as well as differing tones and thematic goals. That's all to the good. Still, I chose to read only a few pieces each week, in between other books and activities, as the turn-of-the-century writing style and the often superficial characterizations were overwhelming when sampled en masse.

But let me get to the stories, of which a number proved intriguing and entertaining. Certainly there are recurring themes here, a principal one being a male hypnotist jealously working to bring about the ruin of a romantic rival (and sometimes ruining the woman in the process). The villain of Julian Hawthorne's "The Irishman's Story" is Dr. Gramery, a mesmerist with "brilliant eyes" – they nearly all have brilliant eyes – who is particularly cruel in seeking his revenge. J.E. Muddock's story "The Crime of the Rue Auber" offers another amoral antihero, where a man hypnotizes his wife to kill his mistress's husband in a kind of two-birds-with-one-stone auto-suggestion. Similarly, "The Playwright's Story" by Willard Douglas Coxey follows a scribe who uncovers an affair between his actress wife and her stage partner, and hypnotizes the man to strangle his wife onstage.

Men aren't the only people to wield deadly power here. The woman with the mesmerizing eyes and the dark, fearsome beauty often manages to kill a succession of men in these stories, either to receive life insurance money (as with "Philip Darrell's Wife" by B.L. Farjeon) or simply to destroy males like a black widow spider (see the entry from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, "John Barrington Cowles"). A variation on the latter, and one of the best stories in the collection, is Erckmann-Chatrian's atmospheric "Suggested Suicide," which is unique because the male witness watching a witch-like woman control and kill lodgers staying at an inn learns the rules of hypnotism so he can turn the spell on the caster.

There are two short sketches by Ambrose Bierce included here, and one is the most comical story in the group, simply called "The Hypnotist." A mischievous narrator finds creative ways to bump off those he dislikes, convincing a prison warden that he is an ostrich, who then swallows "a great quantity of indigestible articles mostly of wood and metal", and making his scheming parents believe they are warring broncos.

Death by Suggestion makes for fun reading and provides an interesting look at how popular culture was translating the exoticism and dangers of hypnotism in the late 19th century. I'm grateful to Mr. Hartman for providing me with a copy of the book in exchange for this (hopefully clear-eyed) review.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed