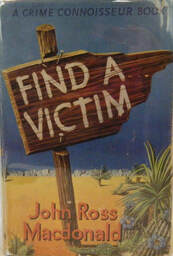

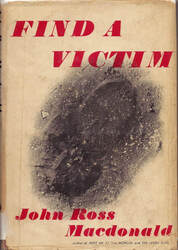

Suspicion for the murderous heist quickly lands on a bar and motel owner named Kerrigan, whose unusually large and insured order of liquor could give him the payday he needs to leave his wife and disappear with Anne Meyer, a girlfriend he employed at the motel. But Anne has been missing for a week prior to the theft, and a small-time hood named Bosey knocks Archer out to dissuade him from further investigation. Undeterred, the detective collects two additional suspects who may have roles in a potential conspiracy: Las Cruces’ Sheriff Church, who might be bending (or breaking) the rules of law and order, and Anne Meyer’s father, who owns the trucking company and is rumored to have sexually attacked his daughter when she was a teenager. The tragic solution pays neat tribute to the Stephen Crane quote MacDonald has chosen to preface the story:

“A man feared that he might find an assassin. Another that he might find a victim. One was more wise than the other.”

And yet the story proves a little elusive even as it is mostly logical, and there are not many characters sympathetic enough to justify Archer hanging around and being routinely threatened and roughed up. Tony Aquista, the dying truck driver, makes a dramatic entrance but leaves a fleeting impression. Kerrigan, Bosey, and an on-the-run druggie named Jo Summer all appear slippery, corrupt, and not worth redemption. Only one person seems worth defending: Hilda Church, the sheriff’s vulnerable wife and sister to the missing Anne.

Narratively, Lew Archer does not need to ambush and kill in cold blood a quartet of criminals who have double-crossed Bosey, but he does just that. Mike Hammer would approve, and apparently the editors at Knopf did too. (Two notes: the fated bandits are characterless, only appearing in the ambush scene so MacDonald can meet his Spillane quota; and this is the first time in the series where Archer shoots to kill in a situation other than one of self-defense.)

At the plot’s conclusion, MacDonald is firmly back to writing what he intended and what he knows best. There is a melancholy, almost a pity generated for the characters left standing, people who made poor but understandable choices and are now paying the price for it. Find a Victim isn’t a bad Lew Archer book, it’s just not the cohesive, contemplative one that Ross MacDonald would have delivered if he had been left alone and allowed to craft another independent, high-quality story without editorial interference.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed