Charles Swinburn is an ordinary man under extraordinary pressure: his electric motor manufacturing company is feeling the squeeze of a national recession, the woman he is courting won't commit to marriage without the promise of a secure future, and the good men who serve as his employees rely on the factory for their livelihoods. Appeals to Andrew Crowther, Charles' elderly and ailing uncle, fall on deaf ears, and Andrew refuses to give his nephew an advance on his inheritance, even though not doing so places the family business in jeopardy. (Andrew accuses Charles of improper management, although the reader understands that external economics are to blame.) After other alternatives have been exhausted, Charles starts to consider methods for speeding along his aged uncle's impending demise.

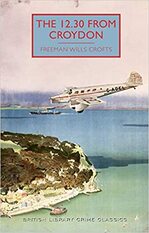

Charles has a sister and brother-in-law, and it is in Peter Morley's presence that Uncle Andrew expires, after taking a fatal pill disguised as an indigestion tablet. Complicating matters for the police, but initially strengthening Charles' alibi, is the fact that death occurs on an aeroplane, as the family (minus Charles) flies across the Channel to Paris to attend to an emergency. For a short time, the reluctant murderer believes his actions to be a success; however, it isn't long before another party puts the pieces together and tries a spot of blackmail, forcing Charles to plan a second and darker murder.

What struck me throughout was how carefully and purposefully Crofts makes his antihero a sympathetic but still amoral character. Charles Swinburn becomes a premeditated killer by degrees, and the author gives him a strong sense of ethics and intelligence, the latter allowing him to rationalize his choice to go against the former. This is the opposite of an uncomplicated sketch of a villain, one who only needs to get the plot started through his scheming, and I appreciate Crofts' attention to detail. Charles tries multiple avenues to raise money to save his company and keep his men employed, and when he first wishes that his old uncle would die sooner rather than later, a strong moral compunction pushes the thought aside.

The obstacle, too, is formidable and unyielding: Charles tries to reason with Andrew and indeed makes persuasive arguments and appeals, but the old man does not relent. The reader goes on much the same journey as the protagonist, which really provides added dimensions to a story that could have been delivered as a routine and emotionless police procedural.

That procedural aspect does come in at the end, when Inspector French – who we are told has just been promoted to Chief-Inspector – recounts the steps taken to build a case for the prosecution away from Peter Morley and right to Charles. This conversation happens over the final two chapters and is told anecdotally over a round of drinks with a reporter, a police captain, and Charles' own defense attorney (after the trial, I should clarify). It's also merely informationally interesting and has none of the dramatic propulsion of the central story; perhaps this isn't a surprise since it is literally a scene of explanation and anticlimax. Crofts keeps his detective very much at the periphery during The 12.30 from Croydon, which works very well here but which I suspect is atypical within the series. Along with the smart sustained build in following Charles Swinburn's steps to murder, the criminal trial is the other dramatic highlight, a wonderfully observed sequence of hope and despair for the accused, with the reader invited to view proceedings from his nerve-frayed perspective.

One other observation: it is clear that Freeman Wills Crofts has an affinity for all things mechanical, and the trans-Atlantic flight, this one seen through the eyes of a 12-year old girl, is described in wondrous and accurate detail. Young Rose Morley experiences the thrill of ascent, the wheels spinning until they no longer touch the ground, then the cabin tilt and the engine noise leveling as the plane's speed allows for a break in the sound barrier. It must have been quite entertaining for readers in 1934, most of whom would likely find travel by air as great and mystifying a novelty as Rose does; Crofts provides the details and makes sure they are right.

I, on the other hand, was wrong. I am quite happy that my prejudices were challenged and that my first Freeman Wills Crofts story was a strong and surprising one. I plan to pick up another Inspector (or Chief-Inspector) French mystery at some point, and I shall see what the mathematic ratio of characterization to timetable analysis will be then.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed