Enthusiastic independent publisher Dean Street Press is in a class by itself, having released dozens of intriguing GAD e-book titles that might otherwise be lost to time and memory.

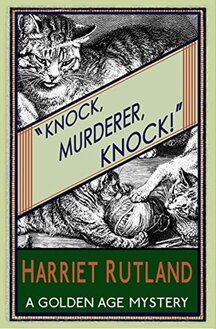

The detective novels of Harriet Rutland, the pen name of British writer Olive Shimwell, are also available again to readers via Dean Street. 1938's Knock, Murderer, Knock was the first of her three mystery titles, and in summary it's a doozy: a serial murderer runs loose at Presteignton Hydro, a health spa on the Devon coast. The killer's preferred method: a steel knitting needle stabbed into the back of the head. There are a lot of suspects (and victims) to choose from, many of them eccentric and/or disagreeable. Gossiping and passing judgment are favored pastimes of the mostly aged residents, while the younger staff bide their time in repressed romances and recognizing the general dissatisfaction with their station in life.

When a young woman guest who has stirred up minor scandal at the spa (through her modern dress, her public reading of passages from Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, and her attentions toward another resident) is found dead, Inspector Palk investigates and soon arrests his main suspect. But then another death occurs, and another, and it is not until a strange amateur criminologist named Mr. Winkley arrives that Palk is able to see the pattern and identify the true culprit.

Knock, Murderer, Knock was chosen this month for perusal by the Reading the Detectives group over at Goodreads, and I thought it would be a great time to be introduced to this author. In retrospect, I am very grateful for the group's multiple opinions, because if I had read it alone I would have felt like a notable outlier. Knock, Murderer, Knock comes highly recommended from such trusted GAD critics as Curtis Evans and J.F. Norris; Evans writes in his preface that Rutland could be considered an “heir presumptive” to such Queens of Crime heavyweights as Christie and Sayers.

It is rare when I find it a challenge to push through a Golden Age mystery story, but multiple times the urge to quit reading was strong. The first five chapters were particularly rough going, as a large cast of characters weaves in and out of the narrative, with no central person or event coming into focus. Worse, they are unlikable, petty people, and worse yet, Rutland uses her third person omniscient perspective to make arch, judgmental comments on her creations.

Further, the characters don’t behave in any realistic way under their circumstances; I can suspend disbelief mightily to enjoy the often fantastical genre of detective fiction, but Knock exhibits unsatisfying story details that speak to the novice status of its author. Examples: there are multiple violent deaths at a guest spa – including two families who lose a child – and everyone passively chooses to remain there? (There is also no real discussion between staff of leaving or shuttering the facility, or of being shut down.) A killer claims a third victim in an identical attack, and the reader learns that the first suspect is still being held after all this time? (Time is also surreally unbelievable if you look too closely at the timetable of a secret engagement and marriage between two Knock characters.)

And while I greatly enjoyed learning from the Goodreads group about the lethal potential of period metal knitting and tatting needles, none of us there could comprehend the handle that Rutland claims the murderer uses to drive in the weapon. Part of the problem is that in the dénouement she makes poor Inspector Palk describe the object using different mechanics, one on top of another: it apparently acts as a retractable-coil toilet roll, or a screwdriver base, or a holed luggage handle, take your pick.

Such criticisms would be far easier to forgive if I had felt like my stay at Presteignton Hydro had provided some satisfaction or rejuvenation by the end. Instead, it was not unlike a camp vacation gone sour, being surrounded by disagreeable guests, checking one’s watch frequently, and losing faith in the events manager to deliver a competent itinerary. For the record, of the Goodreads thread respondents five people enjoyed it, four did not (adding myself would make five), and two readers noted a mix of appealing and off-putting elements. You can also check out Kate's cautiously positive review over at crossexaminingcrime. It is a certainty I will be back to read more books from authors represented by Dean Street Press… just not any more from this one.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed