Indeed, the comments on Chapters 16 to 20 cover much familiar ground first trod in prior posts, and it’s nice to track these topics to a close. Nature, narrative, fate, and foreshadowing are all used effectively by author Gladys Mitchell, giving the reading group contributors much to talk about.

BACK TO NATURE

Martyn Hobbs was less taken with the riding scene and its ballyhoo, commenting that “The hunt seems something of an unnecessary digression, although perhaps it’s just my distaste for aristocratic and upper-class blood sports. It bored me while I was hankering for the conclusion.” He adds that “It does allow for a quick Wilde allusion” quoted in the book by Jonathan Bradley: ‘The unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable.’

I felt that the fox hunt – whose description and sequence in the book turned its focus away from the barbarism of the sport and towards Mrs Bradley’s medical ministrations of fallen riders – was a fittingly active metaphor for the pursuit of the villain(s) by detective and police.

Chris B. and Martyn saw much renewal in the imagery and plotline of this story. Chris continues an earlier conversation with these thoughts: “Returning to the novel’s thematics and recurrent motifs, I’m increasingly convinced that although it appears to be a ‘Christmas’ mystery, it is really an ‘Easter’ narrative in which everything revolves around resurrections, disinterments and exhumations. The earth is repeatedly made to yield up what has been hidden in it: foxes, badger cubs, plant life – concluding with the wild strawberry of the last lines – dog leashes, Bill’s corpse, a typewriter, dogs and cats, and most unusually through a kind of staged ritual Ed Brown himself, who is seen to ‘die’ into the earth and then be lifted out of it so that he can be ‘resurrected’ later, in an obvious parody of the Easter myth and of the death/rebirth of the ancient vegetation god.”

Side note: of this plot turn, José explains how the deception continues: “We learn that Ed was hiding in Will North's cottage to keep up the deception that he was dead while letting the rumour circulate that his corpse had been seen by the police doctor.”

Martyn was following the same thread, commenting that “The final paragraph is given over to innocence and the resurgent spring”:

They were standing by Will North’s cottage. In Farmer Daventry’s field a lamb cried out for its mother. A blackcap flew out of the lilacs and pecked around the cardboard top on a bottle of milk. The lush land rose to a hawthorn hedge, the stable tower, and the trees. Behind the house, on the woodland bank, the wild strawberry ambled in faint flower.

José from A Crime Is Afoot has provided excellent, detailed summaries of each section read by our group, and by necessity I have only been able to incorporate a few lines each week into our sprawling discussion posts. He has created a blog entry offering a comprehensive summary and his critique of Spinney over at his site, and you can visit the page by following this link!

Mindful of spoilers, José explored the story threads just before Mrs Bradley’s reveal of the murderer. One of these threads is tied to a dog, Will North’s astute and aptly named canine Worry. José writes: “On their way home from the Fullaloves' bungalow, the dog was terrified upon reaching Groaning Spinney. Worry wouldn’t go through the gate until his owner arrived.” He provides Mrs Bradley’s explanation of Worry’s worried reaction: “The dog hated that gate; he didn't see a ghost that day but smelt someone he didn't like.”

The ultimate fate of Tiny Fullalove’s absent dogs and cats, revealed in Chapter 20, and the owner’s behaviour throughout proved satisfying to Countdown John, who maintains Countdown John's Christie Journal. While I don’t want to spoil anything by offering specifics, Countdown John says he enjoyed one related clue that was provided in a much earlier chapter and Tiny’s reaction to his animals, showing a compassion that he doesn’t seem to extend to humans.

Speaking of clues seeded in earlier chapters (and of treading lightly to avoid spoilers), Joyka also admires the author’s ability to give the reader information at the beginning that proves right by the story’s conclusion. Joyka writes, “I stand by my original statement that many of the clues necessary to solve the puzzle were present in the first section. Motives were hinted at, and the suspects were presented to us… from the outset.” She then outlines six early observations that prove relevant during the puzzle’s solution, concluding that they are “small clues but very obvious when you look back.”

MRS BRADLEY’S MACHINATIONS

And about that famous (or infamous) intuitive streak Gladys Mitchell bestows on her sometimes superhuman detective, it certainly is a trait that can prove both frustrating and fascinating to a reader. Tracy feels that the series detective’s flashes or insight are tempered by her determination to collect all the clues. Tracy observes that “Mrs Bradley may be just as intuitive as many female sleuths but she digs for the clues and is persistent. I like a persistent sleuth. The only negative is that she likes to talk a subject to death but then not share all of her results.”

As the group discussed in the previous post, the conversations in Groaning Spinney (and other GM mysteries) involving theorizing and speculation that fail to resolve or even move matters forward can overwhelm and confuse a reader. But these passages can also be helpful (i.e., summarizing events and clues to date) and entertaining. Martyn found the scene between the psychoanalyst and the Chief Constable surprisingly agreeable, describing it as “a lovely playful dance of conversation, of question and answer, quite unlike the endless speculation of previous ones.”

JUDGMENT AND JUSTICE

Joyka notes, “I have remarked before that Gladys Mitchell rarely brings her murderers to trial.” She mentions a surprising exception to the rule in the author’s first published Mrs Bradley story Speedy Death (1929) but of Groaning Spinney observes that Mitchell “stays true to this tradition in this book and even [has Mrs Bradley] remark that she ‘dislikes the thought of hangings’.”

Countdown John says that, once it’s fully revealed, the murder method employed on Bill Fullalove “is both literally and metaphorically chilling.” It is indeed a particularly cold-blooded crime, and John observes that “Mrs Bradley is not in a merciful mood, but is still surprised by” an unforeseen double killing even as she connives to “deliberately frighten [one character] to death.” Countdown John concludes that Mrs B “has her own notions of justice, somewhat aligned to those of J.J. Connington's Sir Clinton Driffield (see Murders in the Maze and The Mystery of Lynden Sands).”

Martyn was tracking both the Shakespearean and Greek tragic echoes between the book’s characters. He observes that “There is lovely play between the cultured detective and the changeling Ed (he is Caliban to Mrs B’s Prospero, straying away for a moment from A Midsummer Night’s Dream). But although Ed had ‘never heard tell’ of Arkady ‘in these ‘ere parts, as I knows on,’ he has his own poetry when he warns, ‘you didn’t ought to call up sperrits from the vasty deep.’ Chris recognized Ed Brown’s colorful line as “Glendower’s boast in Henry IV Part 1 (III, i). Adds Chris, “Mrs Bradley’s reply, ‘Only the deadly nightshade from its flowering bed’, with its further allusion to Titania, is meant to sound like a Shakespearean quotation, but is not: deadly nightshade is never mentioned in any of Shakespeare’s works.”

Martyn continues, “Mention of Arcady seems to put Mrs Bradley in a Greek frame of mind, and twice in these last pages she quotes ‘in solemn and sonorous Greek’. Picking up on the Greek theme (and, by the story’s conclusion, multiple off-stage deaths), the Chief Constable observes of Mrs B, ‘I won’t ask by what means you’ve taken the place of the Furies’. And at this late stage, she concedes her fallibility: ‘I did not foresee’ [the fate of two characters].”

LITERARY TURNS

Throughout multiple group readings, Chris and Martyn have been alert to identify allusions from literature and history. I appreciate their sharp eyes and their tireless research efforts.

For me, one reason I return to (and champion) Gladys Mitchell’s writing is the joy I find in her prose style and her evocation of landscapes. It aligns with the appreciations that Chris and Tracy share in their comments above (see Back to Nature), and it runs through Martyn’s admiring observations that follow. He finds, as I do, that “Mrs Bradley’s country walk to meet Ed Brown contains some fabulous descriptive passages. There is a vivid particularity and specificity to the scenes. GM fixes us in the very spot:”

The sky was blue and the slight clouds were high; here a stream ran, and there a bird flew suddenly out of a coppice… Here and there in the valleys a chimney smoked or a small train puffed… Here was a terraced town… and here was a huddled village…

Both Chris and Martyn noticed the title of Chapter 19, ‘Goblin Market’, and connected its reference to “Christina Rossetti’s hallucinatory, weird, and wonderful poem” (Martyn). Chris reports on the quotation ‘Yet there, where never muse or god . . .’: “These verse lines are quoted from the poem ‘Genius Loci’ by the minor English poet and novelist Margaret L. Woods (1855-1945). An error has crept into the opening line, whose second word should be ‘here’.”

And, as with the fox pursued by hounds mentioned earlier, Chris finds another animal metaphor perfect for detective fiction. “‘The bleating of the lamb would tend to excite the tiger’: adapted from a line in Rudyard Kipling’s school story Stalky & Co. (‘The bleating of the kid excites the tiger’) which had become one of Gladys Mitchell’s favourite quotations: versions of the same adage had appeared previously in Laurels Are Poison (Chapter 2) and Tom Brown’s Body (Chapter 20).”

REACHING A VERDICT

This book is notable because Mrs Bradley is allowed to state her case and reveal the villain(s) in Chapter 18, two chapters before Groaning Spinney concludes. I was still engaged by the story, partly because the detective’s admission that there is not sufficient evidence to arrest her quarry means that she must act to force a resolution. (See Judgment and Justice above.) But the structure is a little unusual, and other readers may have a different experience. Of the last chapters, José comments that, “as far as the investigation goes, they don't really add much.”

Martyn points to another Tiny-related enigma. He asks, “What reason or motive is brought forth to justify the extravagant set piece of Tiny’s failed break-in? Mrs B only offers ‘he came to tell me that he was in possession of information that would incriminate [another character]’. All well and good, but couldn’t he have rung the doorbell like other callers without damaged knees? And was the commando knife strictly necessary?”

Curiously, even with such lapses in logic and confusions of detail, one can still have an enjoyable time with a Gladys Mitchell story. Here are some final reader reactions to this book:

Martyn – “The plot feels satisfyingly resolved, with perhaps any troubling details happily forgotten.” (See above.)

Joyka – On the identity of the villain(s) and their relationship(s) to other characters: “That was a surprise!”

Tracy – “Many reviewers don't like Mrs Bradley but I do. I like that she is different and older but without being a Miss Marple clone. I like Miss Marple and I love Miss Maud Silver, but there is room for all types in the mystery genre.” Groaning Spinney was “not my favorite. Of the four I’ve read, Sunset over Soho was the best, in my opinion.”

José – “[Sometimes] I can't figure out how Mrs Bradley comes to any conclusion and I wonder what I am missing. On the positive side, the strength of the story resides mainly in the portraits of the characters and in the description of the environment in which the story takes place.”

Countdown John – “Overall, I'm not a massive fan of Mrs B. I'd picked this up secondhand primarily because it was published as Murder in the Snow - A Cotswold Christmas Mystery and it isn't really a classic Christmas country house case, which is what I was expecting. However, it was better than the titles I've read most recently such as Death and the Maiden and The Twenty-Third Man.”

Thank you to the many wonderful contributors who shared their thoughts and discoveries on this Gladys Mitchell detective story, and thanks to everyone who read Groaning Spinney along with us and visited this site.

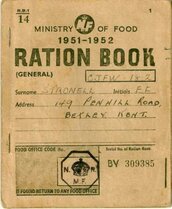

The next Mitchell Mystery Reading Group event will take place during the summer of 2022. I want to stay in this decade, so please recommend a GM book or two that you would like to (re)read that was originally published between 1951 and 1959. You can find a list of titles here, with many interesting Mrs Bradley mysteries appearing in those years. Post your title recommendation(s) as a reply below or email me at [email protected] . Happy New Year to all!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed