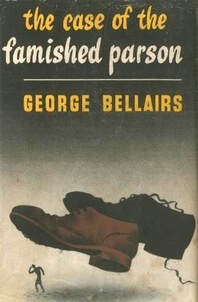

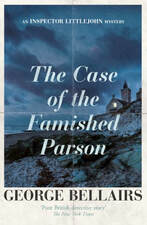

Part of the problem, in my opinion, is that much of the potential of plot, character, and place is diluted by development and resolution that feels simultaneously blunt and generic, qualities that the setup neatly avoided. For example, the bishop’s eccentric family is never brought into focus enough or given enough stage time to be contenders as suspects, and the explanations of both the victim’s starved state and the motive for murder are oddly insignificant. In particular, I was frustrated by a very unconvincing monologue confession from the guilty party that runs on for pages; this is the kind of tin-ear philosophizing where the villain recounts every action and rationale to a hapless listener who is to be dispatched post-speech. At one point, this character actually says, “I don’t know why I’m telling you all this.” In that artless moment, I knew narratively why it was happening but still wondered the same thing.

Curiously, the book as a whole is very reminiscent of the Inspector Maigret storylines penned by Georges Simenon, and similarities are found in The Famished Parson’s strengths and weaknesses alike. Inspector Thomas Littlejohn is quite Maigret-like, an intuitive outsider whose profession throws him into a crime-infused environment but who chooses to never fully integrate into that world. Like Simenon, Bellairs seems to be less interested in fair-play narrative structure (i.e., presenting interpretable clues to the reader) than in releasing regimented information (e.g., through witness interviews and predicting human psychology) that gradually brings a sequence of events into focus. In particular, the solution to this Bellairs mystery feels very much a Maigret case: it is rooted not in the fantastical but in the ordinary, and not in the mystical but the mundane. Because the story started out so exceptionally, however, the reveal of a surprisingly common motive ended the tale on an anticlimax.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed