Yarrow also interviews the combative Felicity O'Shea, housemaid to Meredith Ayres and, improbably, both common-law wife to Bowman (who was never divorced from his first wife) and an ex-worker at the same electroplating factory where the payroll theft occurred. The Inspector also visits the elderly, caustic patriarch Meredith Ayres, who has contempt for Charles, his nephew once removed, and enjoys watching Felicity upset his house staff. And his ailing niece Mary may or may not have died from a purposeful window draught while staying at his home.

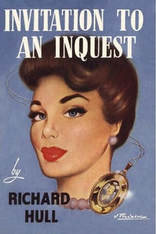

The novel's most obvious flaw is the aforementioned lack of relatable, accessible characters. A story can succeed using unsympathetic antiheroes, but they need to generate some sort of reader interest, even if it's only to see whether they receive their comeuppance. With Invitation to an Inquest, my reaction was consistently "Just get on with it" every time Charles Kerrison provided rambling details of the Night in Question. (The story starts after the deaths of William Bowman and Mary Ayres and the factory theft have occurred, which means that most of the storytelling is passive instead of active, and listening to various versions of what might have happened from one unreliable and conceited witness feels like padding to reach a page count.)

As for Inspector Yarrow of the Yard, he too is a prototype commonly found in Richard Hull's stories: the competent but nondescript police detective, whose job it is to ask questions and yield the spotlight to the more outspoken suspects and witnesses he encounters during the investigation. This tabula rasa approach can also work, but it means that if the detective figure isn't allowed to form a personality and hold his own as a figure of power, then the other characters will need to engage the reader's interest independently. Suffice it to say, that didn't happen for me here.

When one reaches the tepid conclusion and learns the rather silly grand scheme and the motives that the relatives might have had (barely a spoiler: they revolve around inheritance and the fine print in great-grandfather Samuel Ayres' last will and testament), it's difficult not to wish you had spent that time rereading one of Hull's better, earlier books instead. Ironically, Invitation to an Inquest is a fairly rare book to find – I needed to request a text photocopy from the National Library of Scotland after securing permission from the agents who represent the author's estate – but it is also one of the few Richard Hull mysteries (and perhaps the only one; I have four more Hull titles to read) that has almost nothing to recommend.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed