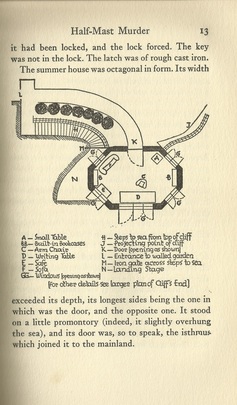

The Murderer of Sleep is a vast improvement over Milward Kennedy’s domestic whodunit from two years before, 1930’s Half-Mast Murder. Where that earlier story revolved around a wearying timetable of people in and out of a summer house and featured the reveal of a rather arbitrary culprit, the plot of Sleep unspools well and makes effective use of its suspects and its setting. The author also uses a lighter touch here that brightly satirizes the detective fiction genre. Take, for example, this charming extended analysis given by Colonel Jethro’s stepdaughter in an early chapter, as she muses on how the great sleuths of the age (manipulated by their creators, Kennedy’s Detection Club colleagues) would go about finding the Colonel’s missing tobacco pouch:

“The only way is to begin at the beginning and work backwards.”

That, after all, she said to herself, was the accepted method in the detective novels her stepfather devoured so eagerly… Father Brown no doubt would have reflected that you buy tobacco for a pouch just as much as you buy a pouch for tobacco, and then he would have concluded that if you could not find the tobacco in your pouch it might be because the pouch was in your tobacco… Well, then there were Roger Sheringham and Lord Peter Wimsey; but they would both want a little help from Scotland Yard, even if, at the end, they were going to show that Scotland Yard was all wrong. No, they would not do; their flippancy would drive her stepfather demented. And so would Poirot: the Colonel had no use for foreigners – particularly Belgians. And Superintendent Wilson would be wise but dull. And Inspector French – well, this would be a case after his own heart; the pouch seemed to have a dreadnought alibi – but it might baffle even French. She shook her head; it was clearly a case for one of her stepfather’s fellow Colonels. How splendid if they could both be employed: for while Gethryn telephoned to “someone in London” to secure (but keep to himself) the vital clue, good old Gore could potter about until someone – the deaf mute in this case – thoughtfully came and told him the solution.

She pulled herself together; this would never do.

Taken in all, The Murderer of Sleep is an entertaining example of mystery fiction from the genre’s Golden Age, from its crime-enticing title to its explanation-fueled confrontation between detective and murderer in the penultimate chapter. I’m glad I awoke and tried another Milward Kennedy novel; this is a good one.

You can also find astute reviews of this book on the websites of Golden Age Detective fiction experts Nick Fuller and Martin Edwards.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed