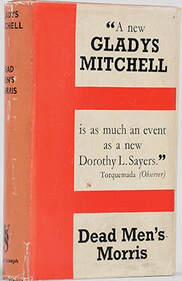

Joyka writes that "characters are very important to me in a book, second only to use of language. Gladys Mitchell hits all of my buttons. I have to say, however, when she is ready to wind up a story, it moves fast. If you want to know more about Carey, Jenny, Denis and the Ditches you will need to read more books. As for the murderer, don’t expect to know the ultimate outcome. Mrs. Bradley has already moved on!"

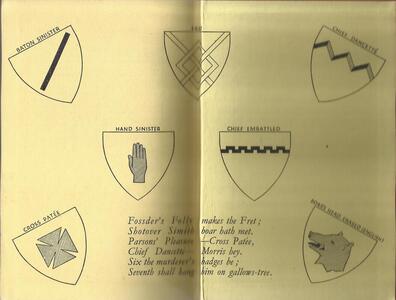

All of this is true, and yet the ending of Dead Men's Morris, for me, is somewhat atypical of the author's usual choice of presentation. I refer to the moment that serves as climax, where an attempt at a third murder – rather quixotically telegraphed through multiple clues by the clever but apparently mentally imbalanced villain – is a rare in-the-present scene of suspense and revelation. Many of Gladys Mitchell's stories are concluded with a dialogue debriefing from Mrs. Bradley rather than a situation where the reader is invited to be witness to action and arrest, so the Morris dance mayhem here feels both satisfying and novel. The psychoanalyst still gets the opportunity to talk in the final pages, but she also physically sidesteps an attempt on her own life and thwarts the attack of another in the previous scene. Personally, I like the choice, and it helps allay my earlier complaint (see Post 2) that the reader is kept at a distance from moments of important action, such as the murders of Simith and Fossder.

The killer's personality remains, by the end of the book, rather inscrutable, and we are invited to literally take Mrs. Bradley's psychological profile of the culprit as the unquestioned truth. I keep returning to the tantalizing comment Mitchell once made about not knowing exactly who the murderer will be when she sets out to write, and that her choice of villain may change as the book forms. Interestingly, the physical clues that point – some would argue that they point too obviously – to the murderer's identity here are established in the first chapters, and no other characters fit the bill quite so well. Yet there is a feeling that, narratively, the killer could have been revealed as one of the other male characters and a few of the female characters as well, and the climax would have been just as, or more, effective than the printed one.

Another observation from Joyka: "My classical literary education sadly pales next to not only Mrs. Bradley, but also Mrs. Templeton, Priest’s landlady. I have no idea which young man pushed a volume of Aristotle’s philosophy down the boar’s throat to escape death. And Mrs. Templeton is a philosopher in her own right, 'Supper first, and gals come later.'"

If additional conversation arrives about Dead Men's Morris in the days to come, I will certainly report it in a separate post. I am grateful that I chose to revisit this story, as it was in some ways more satisfying and thought-provoking than the previous group reading title, 1937's Come Away, Death.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed