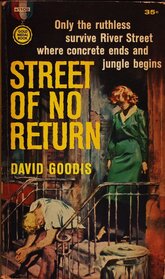

At start, Whitey (nicknamed for his snow-white hair) shares an alley with two boozers who stare longingly at an empty bottle, chiding each other in a Beckettian rhythm about needing to get a full one but making no effort to move. It is Whitey who moves, following a man wearing “a bright green cap and a black-and-purple plaid lumber jacket” from the relative safety of Skid Row three blocks south into the Hellhole, where a race war between Americans (read: whites) and Puerto Ricans has been violently blazing for five weeks. In true pulp noir fashion, Whitey loses the man he was following but comes across a dying police officer in an alley and is quickly arrested for the crime.

What follows is an absorbing and atmospheric nightmare of a tale, with danger and violence swirling around the protagonist and The Fates (or are they Furies?) determined to give Whitey a finish to his quest that ends with his obliteration. And as he moves from one perilous situation to another – with the Hellhole, it is almost literally a case of out of the frying pan and into the fire – this reader became psychologically and emotionally invested in Whitey’s survival to an unusual degree. Like any effective work of literature, that bond with the story’s hero builds cumulatively. I want to know not only how he is going to escape his current high-pressure trap, but also what scenarios lie in store for him around the corner.

And Goodis ratchets the suspense like a master, as Whitey must navigate a world with very few allies and many deadly enemies. Through it all, Whitey is never afraid and certainly never surprised at his circumstances or at the cruelty of men and women; this is just the way the world operates and it would be foolish to expect otherwise. The colorfully dressed man who lures Whitey into the inferno is a fragment of Whitey’s past life: at one time, the Skid Row resident was a Sinatra-like crooner on the rise. But an obsession with a gangster’s girl and a refusal to exit the picture brought about the end of his career and pretty much the end of his life. Now he thinks the man might lead him back to Celia…

The author makes clear that Whitey is standing alone, caring nothing about taking sides in the race war or fighting out of some clouded ethnic ideology. Only one character offers a temporary oasis for the restless loner: Jones Jarvis is an elderly African-American who makes moonshine using scrupulous standards and offers Whitey his shed to recover in after a beating. Like Whitey, Jones is an independent man with his own quiet philosophy, and someone who has found a way to survive despite the violence and corruption all around. As he explains to a recovering Whitey by way of introduction:

“Once when I had a phone they’d get it wrong in the book and list me under Jones. Did that year after year and finally I got tired telling them to change it. Got rid of the phone. Man has a right to have his name printed correct. It’s Jones first and then Jarvis. The name is Jones Jarvis.”

The conclusion of Street of No Return is elliptical and fitting, and it feels truthful to the stylized odyssey that has run its course. It is a story whose details are often punishing and grim: no one in crime fiction takes a more palpable pulp beating than a Goodis protagonist. Teeth are lost, eyes are swollen shut, and vulnerable parts of the body are crushed, literally and metaphorically. There is also little to reassure about the human race and its often dark motives. But David Goodis deserves to be recognized for his writing, a deceptively unadorned prose that comes nearer to delivering a kind of gutter-life poetry. He might not have been a celebrated member of New York’s literary set, but the Philadelphia crime writer undeniably had chops of his own.

Street of No Return is available in a 2007 reprint from Millipede Press.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed