I have been selecting Mrs Bradley books to explore in series order. Our first group reading foray, back in 2018, was a reading of 1929’s The Mystery of a Butcher’s Shop. Every six months or so, a new title was selected and discussed: Dead Men’s Morris (1936), Come Away, Death (1937), Laurels Are Poison (1942), and the wartime Sunset over Soho (1943).

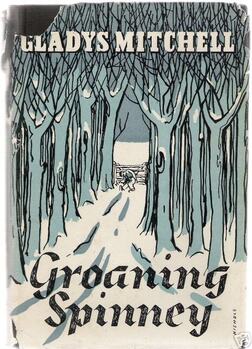

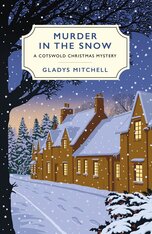

Groaning Spinney displays the author’s transition to a more sedate storytelling style (and a more subdued Mrs Bradley, no longer cackling and poking people in the ribs with a bony, yellow finger). But there is still much to celebrate in this Cotswolds-set holiday story. Over the years, I have read the book three times – the group reading will be my fourth – and each time I am ensnared and held by the author’s charming literary spell.

If you would like to join us for the December reading event, either by sharing your observations or by reading along and visiting the weekly discussion posts, I hope you will do so!

As with previous readings, I would like to divide the chapters over four weeks and discuss one section of the book at a time. To take part, please email your comments (a couple paragraphs or so) to [email protected] by the Tuesday of the week due, and I will create a post incorporating everyone’s remarks shortly thereafter. Here is the schedule for Groaning Spinney:

TUES. DEC. 7 – Comments due for Chapter 1 “Mrs Bradley Takes a Christmas Vacation” through

Chapter 5 “Parson’s Farewell”

TUES. DEC. 14 – Comments due for Chapter 6 “Saturday’s Child” through

Chapter 10 “Peculiar Persons”

TUES. DEC. 21 – Comments due for Chapter 11 “What’s In a Name?” through

Chapter 15 “The Gun”

TUES. DEC. 28 – Comments due for Chapter 16 “The History of Worry” through

Chapter 20 “A View to a Death”

Of course, participants are welcome to read ahead, but please make notes of future chapters and send those comments on the appropriate week. I’m looking forward to revisiting and discussing this book. Let me know if you have any questions. Happy reading!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed