So it seems fitting that this story is narrated by Hilary Fenton, an American male who observes the British college environment with an outsider’s delight akin to an anthropologist. I suspect that Webb was more at home in England than his protagonist here: while the author was born in Somerset and moved to the United States when he was twenty-five, the fictional Fenton is a Yankee abroad. The book boasts a four-page glossary that defines “some of the local colloquialisms and other quasi-technical terms” to bring the uninitiated up to speed. A gyp, we learn from this addendum (although it is also clear in context), is “a male college servant assigned to take care of a certain set of rooms or the rooms on one particular staircase”. And in this story, there is a lot going on in those rooms and on those staircases.

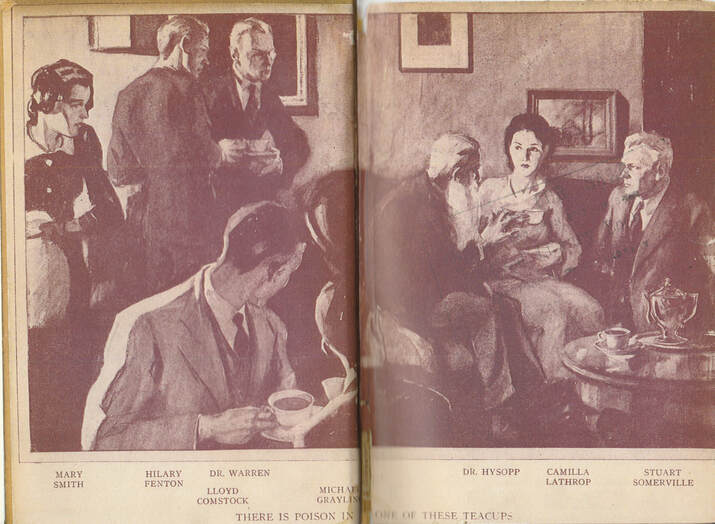

But it is in an ordinary lecture hall that young Fenton first spots his romantic ideal, Camilla Lathrop. He spends the early chapters learning her identity and stage managing another encounter. Fenton also spots her – or thinks he spots her – on the landing outside Baumann’s room on the stormy night of the murder, and it is from a muddled sense of chivalry that Fenton hides evidence that might point to her at the crime scene. He launches his own amateur investigation, all in the name of clearing Camilla, and a second murder at the college builds to a tea party with the Don where one cup is laced with strychnine.

The glossary also informs me that ‘Varsity is “simply an abbreviation of the word University” that has “no athletic or other sinister significance”. This is useful to know, especially when reading a book with an uncertain word in the very title, such as Obelists or Furlong.

Murder at Cambridge ('rah 'rah 'Varsity) is available in the UK through Ostara Publishing and available as an eBook in the U.S. through Mysterious Press/Open Road Media.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed