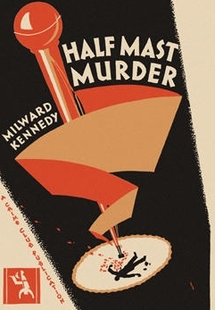

This month the focus is 1930, and my first foray, Mignon G. Eberhart’s While the Patient Slept, never quite overcame its heavy Gothic tone and melodramatic storyline. For my second 1930 mystery, I went in the opposite direction: Milward Kennedy’s Half-Mast Murder is first and foremost a puzzle story, so much so that the novel unfortunately offers little beyond its plotting to engage the reader.

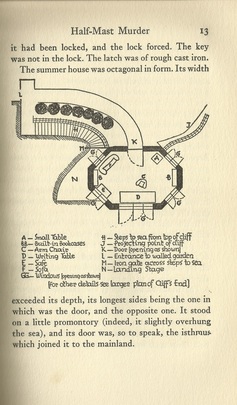

Half-Mast Murder (an appealing title, at least) offers very few literary attributes beyond its detailed, timeline-centric plotting. The first pages start promisingly, with various family members and guests at Cliff’s End racing to the summer house only to find Professor Harold Paley locked inside the room and dead from a knife to the chest. Niece Cynthia notes that the flag above the building is flying at half mast, and promptly faints from the sight.

It is soon thereafter, during the introductions and interviews of the suspects conducted by the nondescript Superintendent Guest, that tedium begins to descend. Each character — from the matronly sister of the victim, Mrs. Arkwright, to the young relative George Shipman and the older business acquaintance Bertram Trent to the undefined American Mr. Quirk — is questioned in turn, and the absence of personality from each speaker makes these conversations as interesting as reading a court transcript after a trial.

Further, there is no real dramatic shaping for these interviews, which is to say that questions start, answers are given, and the superintendent moves on. The information and revelations should lead somewhere compelling on a character level: by the end of the scene, the reader might feel, for example, that the person is highly suspicious or completely innocent, or perhaps a curious statement is made which begs closer scrutiny. This Kennedy does not do. In fact, those early interviews create distinct narrative plateaus, and when he divides an interrogation between chapters, the ending moment that is chosen often feels arbitrary and pointless.

Ending lines from Chapter Three:

“Oh, but I wasn’t the last person [to see Paley alive].”

“Then who was, sir?”

“I haven’t the least idea.”

(Minor, non-specific spoilers ahead, but ones I submit as evidence to show why it is hopeless for a reader to arrive at a fair-play solution ahead of the author.)

Let us take the bustle first. This is a mystery story where a raft of incriminating clues are presented and the solution is tied to an incredible series of well-timed entrances and exits by multiple parties around the victim or victim-to-be. As many as five persons, we eventually learn, visited the professor in the summer house just before, during, or after his death, doing so with clockwork efficiency – 2:30, 2:45, 3:12, 3:17, 4:30, et cetera – and leaving all manner of physical evidence behind. To me, it’s another recipe for tedium, as the gathering and sorting of clues becomes tiresome when a muddy footprint and a pair of blood-smeared swimming trunks serve to cancel each other out when it comes to identifying the murderer. A few red herrings in any mystery are welcome, but this puzzle’s artificiality and inconsequentiality are made apparent with the explanation of each (eventually unimportant) clue.

I am thrilled to keep discovering new authors from mystery fiction’s Golden Age, but it will be a while before I raise the flag on Milward Kennedy again.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed