Ironically, it is Clinker who outlives his owner. After threatening to challenge the entire will due to Samuel Laxter’s intolerance of a cat, Charles Ashton’s body is discovered in his room. Clinker’s muddy pawprints lead from the open window onto the bed. The cat’s presence seems to implicate Douglas Keene, a young architect and boyfriend of the disinherited Winifred Laxter. Keene was seen leaving the house that evening as he carried Clinker, and if he left the grounds after the cat came into the room on that rainy night, then he becomes the prime suspect in Ashton’s death.

As it often happens in Erle Stanley Gardner’s busily plotted stories, the entanglements and complications build steadily, and Perry Mason must be both proactive and defensive to arrive at the truth. Among many questions to answer: was millionaire Peter Laxter killed by carbon monoxide gas piped into his bedroom before he perished in a house fire? Who was a man named Clammert, who had access to a critical safety deposit box? And who killed Edith DeVoe, an attractive nurse who might have known more about the Laxter household than was healthy for her?

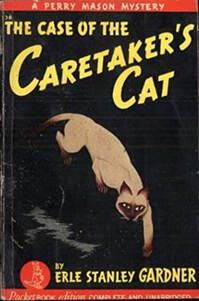

As with the other series titles first published in the 1930s, The Case of the Caretaker’s Cat is lively in pace and impressively, almost intimidatingly complex in plot. Author Gardner has a marvelous gift for keeping the pot boiling, and I would be hard pressed to recall a single scene in any Perry Mason book from this period that didn’t advance the story and offer a new piece of information to be puzzled over. That breathless pacing can be a bit fatiguing, but it also offers the reader more twists per page than can be found anywhere else.

Even better, this is the first of the early Mason titles whose prose feels unlabored and genuinely effective, as if Erle Stanley Gardner had hit his stride and found a way to balance the writing and characterization to accompany his often brilliant plotting. There seem to be fewer unnecessary “Perry Mason asked” and “Paul Drake replied” dialogue identifiers than in previous books, and some of the author’s paragraph descriptions are nicely evocative instead of feeling stilted.

Caretaker’s Cat is also the first book to fully explore the relationship between Mason and his smitten, capable secretary Della Street. In an entertaining extended storyline, the lawyer asks Della to join him to impersonate a honeymooning couple, and she inhabits the role with verve. If there’s an of-the-era sexism to the stereotype of the pining secretary, it’s nicely offset by Della Street’s fierce intelligence on display. In the courtroom climax, for example, Street is called to the stand to be questioned by opposing counsel and acquits herself admirably, showing that she can parry and equivocate as heartily as her employer.

Speaking of characters and their strengths, Winnie’s Waffles entrepreneur Winifred Laxter may stand as a stereotypical pillar to support the plotline – she’s the respectable ingenue who rejects her amoral family only to find that she and her fiancé are being pulled in once more, this time as murder suspects. But Gardner presents the lovers’ plight in a simple and sympathetic way, and she and Douglas Keene are the innocents that we, and Perry Mason, want to see exonerated and brought together by story’s end.

Finally, this case offers some wonderfully twisty Perry Mason dodges and courtroom revelations. There’s a doozy of an alibi where Gardner orchestrates a clever reversal, essentially one relying not on where the suspect was at the time of a murder but rather where the victim was.

The reason for Mason’s newlywed masquerade – and his sending of fake telegrams and his reporting of a stolen car that was never missing – is to flush out an incognito character for one last final-chapter surprise. As always, nothing feels particularly true to reality in a Perry Mason case, but we have headlines and Dostoevsky for those types of stories. And when we want muddy paw prints that lead the police to a corpse and Mason to a murderer, then Erle Stanley Gardner will reliably and delightfully deliver.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed