If a greater philosophical theme or social or cultural commentary emerges from this melodramatic foundation, then the results often become exponentially more interesting. Marie Belloc Lowndes' classic 1913 suspense story The Lodger, which presents the tale of a landlady who suspects that her tenant might be a Ripper-esque serial killer, neatly uses its plot to explore the alarmingly knife-thin line between public, societal respectability and private, destructive criminal deviance.

Police detective Lance O'Leary arrives on the scene and, through the course of a second murder and the repeated purloining and recovery of the jade elephant, manages to spend a remarkable amount of time on the spooky Federie property. Eberhart dresses her haunted house with dusty, heavy curtains that partition most of the rooms (unless one needs to be locked to further the plot) and no electricity, allowing oil lanterns to regularly grow dim and fill the rooms with oppressive shadows and darkness.

The book's sturm und drang genre tone is so determinedly consistent that its author doesn't really have anywhere else to go. When every scene is fraught with potential menace and suspicion, only moments of action and occurrence can offer a true effect, such as an attack on the heroine or the discovery of a body. The pitch of melodrama is usually notoriously high, and as such is often hard to sustain effectively. The simple act of looking out a window now calls for prose at once atmospheric and needlessly hyperbolic:

From the window in the hall, beyond the wet path and dreary iron gate, I caught a glimpse of an ambulance. It loomed coldly white through the dismal, gray dawn. The sleet was turning again to heavy fog. The shrubbery, bare and brown and dripping, mingled indistinctly with the shadows of the fog. Toward the north of the house the dense thickets of evergreens made black blotches. And all about the place reared that solid wall, hemming in the evergreens and the shadows and the lifeless garden and the grim old house in which I stood, where murder had walked that night.

This is not the only frustrating transgression to be found within Eberhart's plot: the final-chapter reveal that a character owned an unknown duplicate set of house keys renders the earlier mystery of access to locked rooms irrelevant; and, amusingly, we learn only at the very end that two characters possess similar sounding voices, and that an early conversation heard by the observant Sarah Keate is actually now attributed to a different individual than she had claimed. How any reader is supposed to get ahead of this bit of transcribed aural trickery is beyond me.

If a contemporary puzzle fan has not yet launched the book across the room in frustration, he or she is treated to this stratagem from the handsome Lance O'Leary. After the murderer repeatedly rebuffs the detective's accusations by saying "You can't prove anything," O'Leary lays this cunning trap (the dual pronoun use to avoid revealing the villain's gender in the excerpt is my own addition):

"There is only one thing I am curious about," said O'Leary quietly. "How did you get that revolver over in the corner of the vacant bedroom upstairs without entering the room yourself?"

[The murderer] smiled; it was an ugly smile.

"I threw it!" [he/she] said with a grisly touch of triumph in [his/her] voice. "Had you there, didn't I! I simply opened the door, rubbed the fingerprints off the revolver, and threw it." A look of terror came into [his/her] face. "No, I didn't! No, I didn’t! You can't prove anything."

"You've confessed, you fool," said O'Leary in a tone as near savagery as I've ever known him to use.

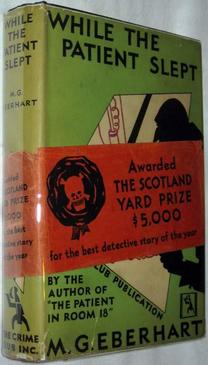

An interesting and equally unbelievable postscript: according to the image at right, this title received the Scotland Yard Prize for best detective story of the year, ostensibly beating out several other titles in the running for 1930.

This review was inspired by the Crimes of the Century year-by-year reading challenge, which can be found on Rich's great mystery fiction community website Past Offences.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed