One of the new group members is José, whose mystery fiction website A Crime Is Afoot provides a wealth of biographical information and book reviews in English and Spanish! José offers a summary of Groaning Spinney’s plot, which I will quote in part as we explore different aspects of the novel. At Christmastime, Mrs Bradley visits her nephew Jonathan Bradley and his wife Deborah (née Cloud) at their country house. Always one for physical activity, the new arrival is soon hiking through the surrounding landscape.

This story is always a pleasantly evocative one for me, with setting and climate particularly effective to conjure up a mood both comfortable (inside by the fire) and cold (outside in the snow). Claudia also notes the author’s ability to bring her tale to life. She comments that “The description of the winter conditions rings very true. There was some eeriness in Gladys Mitchell's description of the approach to the ghost gate. She has a light touch that adds to the atmosphere."

A COTSWOLDS CHRISTMAS

The memorable scenes of Mitchell’s characters interacting with the hills and fields (and the winter weather) of the southern West Midlands landscape of the Cotswolds is one reason why Groaning Spinney remains a favorite title for me. Erin C. feels similarly: “The description of the characters in the book trudging around in the snow put me right out there with them. I could feel the wet, cold clothing and the effort it took to move in very deep snow.”

For some, Mitchell’s prose descriptions of the land don’t offer a clear picture for readers trying to work out the geography. Hilary W. writes, “Like many of Gladys’s books I find the layout of village, estates, woods, etc. difficult to visualise and get people walking up the Spinney to reach a lower point.

Has anyone drawn out a plan of the environment of this location?” I know that the 1950 edition of the book doesn’t have an accompanying map to help, although some of Mitchell’s earlier books do. GM also regularly used county ordnance maps to plan and plot her books, and geography that was obvious to her with maps for reference may be harder for readers to imagine.

“Unusually for Gladys Mitchell, the village in and around which the action is set is never given a name, although there are similarly anonymous villages in St Peter’s Finger and When Last I Died. The villages mentioned on the novel’s fourth page, however, are all real ones that can be found between Cheltenham and Cirencester, at the Gloucestershire end of the picturesque Cotswold hills. The same applies to the real village of Chedworth, which is briefly mentioned in Chapter 2 as a nearby site of Roman-era archaeological finds. This is Mitchell’s second sustained attempt (after the Oxfordshire of Dead Men’s Morris) at a West-Country milieu in the proper sense, her usually preferred rural locations in Hampshire or Dorset being South-Country.”

SPILLS AND SPINNEYS

And yet this harmless method may have been biased from the start. Upon examination, the shorter taper turns out to be the longer one. Joyka is not convinced: “Eyes that sharp can’t be deceived by a doubled spill!” And Countdown John, who manages Countdown John’s Christie Journal and provides smart in-depth reviews for all stories Agatha, also believes the sleuth’s choice was predestined. He comments, “I enjoyed how Mrs Bradley, despite using the method of chance, really just goes where she wants to - I'm sure if Sweden had been unfairly picked she may have changed her mind.”

Understandably, readers chose to seek out an official definition of the word Spinney; it’s not a geographical term many of us Yanks regularly use or hear, if at all. Claudia knew it referred to a small wood, but consulted Merriam-Webster and was rewarded with this etymological information: “Not only is it a small wood, but it is small wood with undergrowth, which is emphasized. The first known use of the word was in 1597 and is listed as deriving from the Anglo-French word espinei - thorny thicket - which derived from the Latin spinetum - thorn.” So the small wood is built on dangerous ground.

And Tracy K, who reviews classic and contemporary crime stories on her website Bitter Tea and Mystery, wondered about the Groaning that’s attached adjectivally to this Spinney. Tracy observes, “I don't know if that is just because of the moaning and groaning of winds through the trees or points toward a ghost moaning in that area.” For me, both interpretations are valid, and both engage the reader’s senses and imagination in a wonderfully eerie way.

CHARACTERS: FULLALOVE AND INSTANT DISLIKE

From José’s summary: “Mrs. Bradley meets brothers Tiny and Bill Fullalove, and she realizes that neither she nor Deborah like Tiny. However, Tiny and Bill will be joining them for supper on Christmas Day and for tea and dinner on Boxing Day.” Claudia says that the brothers “grab the limelight right away. Dame Beatrice seems to notice everything.” That memorable moniker of Fullalove, reports Chris B., is “a genuine but rare English surname. Jonathan’s guess that it is a Yorkshire name is historically unlikely, the earliest recorded examples being from 14th-century Cambridgeshire and Norfolk.” And Martyn Hobbs notes wryly that “Bill and cousin Tiny sound like a pair of R’n’B crooners.”

From Joyka: “I find it interesting that Mrs Bradley takes an instant dislike to Tiny Fullalove. Deborah gives her reason for disliking him on the way home from their first visit but Mrs B had made up her mind before this… By Boxing Day, Mrs. Bradley has added Bill Fullalove and possibly the choirmaster, Emmings, to the list of persons she dislikes. Mr Mansell and Mr Obury don’t rate very high on her list either. This is very unusual for our Mrs. B, who usually likes young men and gets along well with them.” Martyn identifies a thread that I was following also: “There are enormous amounts of bachelors (one, at least, a widower) in this place, and a few unattached women, not to mention all the trainee-teachers up at the [neighboring] college. It fairly reeks of sexual frustration.”

Mitchell also had a penchant for bringing rustic servant characters to life. In the earlier wintertime mystery Dead Men’s Morris, it was the lively Ditch family and their colorful Oxfordshire dialect. In Spinney, the Bradleys are served by the Blotts, who stubbornly hold to feudal custom despite the bemused embarrassment from their employers. Countdown John says that the author’s “description of the Blotts is brilliant - and how they determine to call Jon and Deborah lord and ladyship based on the previous occupant.”

As for the sleuth herself, Tracy finds Mrs Bradley more of a team player here than in previous books. (Her personality is also becoming more subdued, with Mitchell less interested in portraying her as the terrifying, cackling, reptilian figure she was in her earliest adventures.) Tracy writes, “It is not that she has not participated in the action and discussions, but in this book Mrs B is more of a part of the cast, and not the one leading the investigation. Her forceful personality keeps her involved, of course.”

Martyn noted the reformed figure as well, but still found some vestiges in the text of her former, formidable self. Observes Martyn, “Mrs Bradley doesn’t cackle until Page 51. It was like seeing (or hearing) an old friend. And it is nice to see this rare instance of her sartorial extravagance: ‘…wearing a ski-ing suit she had borrowed from Deborah, enormous gauntlet gloves of her own, and Jonathan’s motor-cycling helmet…’”

PERIOD DETAILS

A life-long educator herself, Gladys Mitchell makes sure that the Bradleys are never too far away from an academic institution. Chris explains that “while Jonathan has acquired the smaller manorial portion of the old estate, the government’s Education ministry has bought the rest, converting its ’huge modern house’ as an Emergency Training College.”

He offers this illuminating context: “In 1945, the UK government had established about twenty teacher-training institutions under that name, the ‘Emergency’ label providing a political fig-leaf for the legally dubious extension of wartime land-requisition powers to postwar civilian projects. Their purpose was to train up a fresh cohort of schoolteachers rapidly so that the expansion of secondary education required by the Education Act of 1944, which raised the school-leaving age from 14 to 15, could be accomplished. In reality, they were set up in large disused buildings in towns and cities, not in remote Cotswold villages, but when Gladys Mitchell wants a training college (as with Cartaret in Laurels are Poison) she goes ahead and invents one, regardless of the improbable location.”

And Hilary sees another then-and-now distinction here, writing that “The teachers’ Emergency Training College and its 13-month course could turn out as good as or better [educators] than the teaching direct-type graduate schemes of today.”

There are more intriguing period details, including the presence of a present that would be especially envied among us Golden Age bibliophiles. As Countdown John says, “Deborah is a lucky woman” to receive “a dozen book tokens - Christmas bliss.”

DEFINING THE ERA

Chris B. provided the following context to pinpoint the story’s date, and the connections he makes between text references and historical details are fascinating. This is what he has shared:

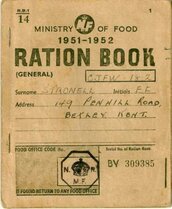

Chris offers these examples: “Jonathan’s initial invitation tempts his aunt with the boast that he has ‘achieved’ a bottle of Scotch, the deliberately evasive verb suggesting that he has acquired it on the black market. Later in the novel, the distinctively late-1940s crime of petrol-theft will make its appearance: the ration per motorist in 1948 was equivalent to only 90 miles of driving per month, thus 3 miles a day, although this would be doubled in 1949 before such rationing was abolished a year later (rationing of sugar and meat continued as late as 1953-4).”

He contrasts this book “with the richly festive Dead Men’s Morris (1936), in which the plentiful provision of food and drink is described with relish. [In Groaning Spinney,] no account of the main Xmas meal is even attempted, probably because descriptions of culinary plenty would too painfully have reminded British readers of their actual privations at the time. Instead, the one meal that is described carefully is the distinctly un-festive stew of tinned meat, beans, and potatoes that Will North serves up for Mrs Bradley in Chapter 5, which more accurately reflects British diet of that time. (It would be entertaining to hear Henri’s doubtless horrified assessment of such a meal, but the opportunity never arises.)”

There is another element that helps to define the era: the author’s depiction – and the attendant strengths – of her male and female characters. While (in my opinion) Jonathan Bradley plays at patriarchal bluster here, it is his wife and his aunt who are in control. (Deborah, we learn, was more than capable of stopping the unwanted advances of Tiny Fullalove.) Erin observes that Jonathan is “a pleasant chap but not as bright as his wife” and “is delighted that Mrs Bradley is still an advocate for strong, independent women in this book. The comment that Miss Hughes was ‘strong-headed’ I recognized as left-handed praise right out of the 1950s; saying that to a woman now would be an insult.”

POETRY AND PROSE

Milton makes a cameo in Chapter 2.

Milton makes a cameo in Chapter 2. “When Jonathan asks Mrs B, barely four pages in, what she thinks of the landscape where he now lives (and the scene of whatever crimes are to come), she offers four adjectives:

‘Desolate, enchanted, apt and supernatural.’

When he asks ‘apt for what’, she responds with four nouns:

‘For treason, magic, stratagems and snow.’”

Adds Martyn: “Snow is guaranteed. Perhaps the other three will be key elements of her story.” Martyn also spots shades of Jane Austen, “for their style and also for their occasional humorous sting.” He offers this example, a line that made me smile when I came to it as well: ‘Mrs Bradley’s three marriages had provided her with a vast and varied tribe of spirited and gifted in-laws, some of whom she liked.’

Claudia investigated the poetry couplets and verses that introduce each chapter. GM often incorporated classical (and sometimes modern) verse into her stories this way, and clearly enjoyed doing so. Incidentally, the use of epigraphs in mystery novels generated some debate recently in an online mystery fiction group. Some readers said that they found the introductory poetry useless and skipped over it; others enjoyed exploring how the sentiments spoke to the plot and tone of the story. Claudia found that each of GM’s selected Spinney poets has “a strong connection with religion and comes from a similar time.” Chapter 1, for example, quotes these lines from William Habington (1605-1664):

‘Go, stop the swift-winged moments in their flight

To their yet unknown coast, hinder night

From its approach on day.

Chapter 2’s quotation is equally concerned with light defeating darkness; Claudia identifies it as part of The Morning Hymn of Adam from Milton’s Paradise Lost:

‘…and if the night

Have gathered aught of evil, or concealed,

Disperse it, as new light dispels the dark.’

I always fine such intertextual connections compelling and often illuminating. But Claudia asks, not unfairly, “As enjoyable as this exercise was, does it mean anything? There is a strong strain of ethics and justice in this series. Not always as you might expect. If nothing else, it gives an insight into Gladys Mitchell's taste in reading.”

THE WOOD BEYOND

We will let José catch us up on the plot before we leave the first five chapters: “The day after Boxing Day, several people in the vicinity begin to receive anonymous letters with false accusations, but they all have a small dose of truth to pass them off as true. [Next,] Jonathan finds the body of Bill Fullalove at Groaning Spinney, [slumped over the gate] in a similar fashion as how, a century ago, the old parson turned up dead.”

And here is where readers are and what they are tracking as we move ahead in the book:

On those ominous anonymous notes, Erin finds the typed letters “intriguing. They are used to move the plot around, literally around, as the characters meet and speak to each other about them. The second letter about the choirmaster is moving us out of the manor house into the church and meetings with other characters. Gladys Mitchell seems to love to add places and people as she moves the story along.”

Perhaps she is adding a few too many people. Martyn reasonably worries, “By the time we reach the end of Chapter 5, the ever-expanding cast of potential suspects and victims could form an opera chorus. How did GM track their histories and plot their appearances in the novel? Did she use charts? Diagrams? I have the feeling that I might struggle to remember all their comings and goings in the upcoming chapters.”

Claudia enjoyed the liveliness of those many characters, adding that “even the animals are fully participating.” As for that mound of disturbed snow on the platform forming a badger’s lookout: “I was not fooled by it. Were you?” Claudia shows a willingness to travel, despite the inclement weather: “The village and surroundings make me want to return to the Cotswolds in winter.”

Joyka recognized in Groaning Spinney an emphasis on action and forward movement, snowdrifts or not. She writes, “Gladys Mitchell gets a lot of criticism about too much description of the countryside in her books. There are not many pages devoted to descriptive text in this book. Action is name of the game! GM lays out not only the characters early in this book, but also all the tangled skeins that need to be sorted. I am sure she has a few more surprises for us but I think GM’s main clues have been presented already.” A tantalizing theory!

Tracy K. offers this encapsulation: “By the end of the first five chapters, a death has occurred, although at this point it has only been declared as ‘death by misadventure.’ Jonathan and the vicar have both received poison pen letters, and they are both very interested in following up on them, figuring out who sent them and why (unlike some mysteries where the recipients hide or burn the letters in shame or fear of exposure).” Tracy concludes: “So far, I am finding this book a good reading experience.”

Countdown John finishes up his comments by asking, “Is Bill's death an unfortunate accident or murder? And if so, how? What was all the business with the letter and key to Jonathan about? And who is writing the anonymous letters?” His verdict? “A strong opening.” And I hope future chapters won’t disappoint, especially for someone so well-versed in the canon of Agatha Christie!

Next week, we will discuss Chapters 6 through 10, as seasons change and plots thicken. Please email your comments to [email protected] on or before Tuesday, December 14. Happy continued reading!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed