As Hull employs his gimmick for Nerves, one of the most intriguing aspects becomes looking for clues within the text where the unknown narrator may show favoritism when describing a particular villager. One would, after all, expect the killer to reference himself in a more flattering light than his peers, especially as we can tell through tone and worldview that we have yet another Richard Hull misanthrope at the center of the tale. Personally, I felt more could have been done with this idea, which would lend itself nicely to some misdirection that the author doesn't seem interested to explore. Similarly, while I would love to continue to say "he or she" in reference to the murderer's gender, the two women characters Hull offers up are each handled so dismissively by the narrator that it's hard to imagine either Delia Keyes (portrayed as a lustful, roaming housewife) or May Benson (drawn as a prudish, humorless spinster) writing about herself in the third person and painting such an unflattering picture, even in private or in jest.

So that leaves the men of Losfield End. Timothy Venner is a nerve-ravaged ex-soldier now engaged in a personal war with the village's extremely loud clock tower; Reverend James Young is a long-winded but cheerful clergyman with a fondness for black-market handkerchiefs; Carlisle is a London broker with questionable prospects and a penchant for model trains; Smee, a farmer now set upon by inspectors from the Ministry of Food, kept losing his livestock until butcher John Hannon disappeared. Delia Keyes' cuckolded husband Norman, the blustering Colonel Waring, and May Benson's long-suffering brother Alec – who is not averse to slipping his sister a sedative in exchange for an occasional night of peace and quiet – also take pleasure discussing the ongoing village events down at The Green Man over a pint.

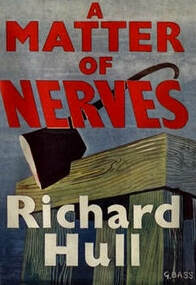

A Matter of Nerves proves to be a very readable story, but not a great one. I am always a fan of self-contained English village mysteries, where the visitor gets to view the occupants and their running about as if they were a colony of ants under glass. The many British irritations and obsessions on display strike me as one of the book's most engaging elements: for example, the Reverend prides himself on the fact that the entire village turns out for his sermons, when in fact the unknown narrator (and, one suspects, many more in the congregation) uses the time in church to muse on personal and criminal matters. May Benson's insistence that everything should happen on a precise schedule, even sinning and time-wasting, is a humorous conceit, and the subplot of a one-man post-war black market that traffics in stolen sheep, Persian rugs, and silk handkerchiefs lends a lighter flavor to a story that starts, and ends, with death.

Finally, I enjoyed the fact that the first-person storytelling allowed me to connect the narrator's guilt of his crime with the very troubled boarder trapped in Poe's famous story, "The Tell-Tale Heart." There's just enough evidence in the text to draw parallels, but not enough to glean anything significant from the comparison. That feeling of missed opportunity and potential present but untapped runs throughout A Matter of Nerves. It's enjoyable, but with a steadier hand and a little more literary ambition, it could have been a late-period classic of detection fiction.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed