"Could not stick two years [at Oxford College], the spectacle of so many quite decent youths being got at and ruined for life was too much for him. Heard that at Cambridge the hearties were still heartier and the intelligentsia even less intelligent, so decided to dispense with any further education… Traveled about for a bit, learning languages. Then settled down for a bit to investigate crime; said it was the only career left which offered scope to good manners and scientific curiosity. He's been very successful; made pots of money. He did all the stuff in the Duchess of Esk's diamonds affair and several high-hat blackmail cases which have figured less prominently in the press."

"But what's he like?"

"Like? Oh, like one of the less successful busts of T.E. Shaw. A Nordic type. He's rather faddy, by the way; his protective mechanism developed them, I daresay. But you must have water perpetually on the boil; he drinks tea at all hours of the day. And he can't sleep unless he has an enormous weight on his bed. If you don't give him enough blankets for three, you'll find that he has torn the carpets up or the curtains down."

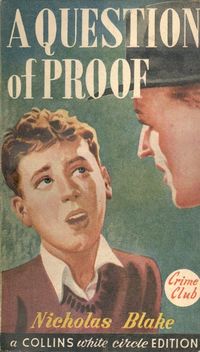

There is a lot to appreciate in A Question of Proof, including lively comic descriptions and characterizations, literary and historical allusions, smart observations about British public school practices and quirks, and (perhaps most importantly) a mystery puzzle plot that stays busy and draws in several suspects before the detective reveals his final-chapter solution. Whether the reader feels that Blake has provided a fair-play puzzle experience will depend largely on how satisfied one is with the stated motive of the murderer. To his credit, the author makes sure all loose ends are tied up and explanations of the red herrings are provided.

Nick Fuller over at The Grandest Game in the World has also examined A Question of Proof (I would expect nothing less!) and has collected contemporary reviews of the book on his site.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed