I mention those time periods and their representative crime literature above – the 1930s and the Golden Age, the 1970s and American police stories, and the serial killer thriller that holds sway today – because Appearances of Death made me think often about societal and cultural behaviors towards mystery stories.

Enter the police procedural. Early practitioners like Georges Simenon and his Inspector Maigret (who started in the 1930s) struck a healthy balance of classic whodunit and a description of the daily duties of a modern police department: witness interviews, fingerprinting, medical examiners, and a lot of legwork. With procedural American authors like Ed McBain and Dell Shannon (the latter was a pseudonym for Elizabeth Linington, a prolific writer of mysteries from the 1950s until her death in 1988), the grit of realism was injected into both the types of crimes covered and the emotional distance of law officers who survey the results of violent crime on a daily basis.

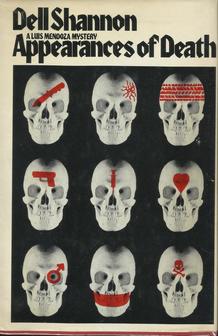

And that was my first realization with Appearances of Death: there are a lot of casualties in the book, and (as with reality) the police only step in after the damage has been done. Both the title and the skull-pocked dustjacket cover are truthful indicators of the story ahead. Appearances isn’t explicit the way that the thrillers of today tend to be – I’ll address this contrast later – but there’s an honest depiction of the randomness and sheer quantity of real-world violence here that depresses me greatly. I love to escape into a Golden Age puzzle because it is spiritedly removed from the reality I know. In Luis Mendoza’s Los Angeles, the days are measured by the number of deaths at the end of the day – from homicides, robberies gone bad, hit-and-runs, rapes turned deadly, and the occasional innocent fatal freeway crash. For me, a little (as in, one Dell Shannon book) goes a long way.

The Robbery and Homicide Division keeps track of it all, and I need to credit Shannon’s skill as a writer that she is able to weave more than a dozen investigations throughout the book, concluding nearly all of them with the apprehension of the criminal(s). There is an admirable variety which, as long as I don’t get queasy from the cruelty of the various acts of inhumanity, is similar to unfolding several short stories over the course of a brief novel. But the cruelty (and surprising misogyny, although Linington was in her mid-50s when she wrote the book, and likely not too politically progressive based on her interactions, criminal and otherwise, between men and women characters) is a tough sell. The problem isn’t that the world she creates isn’t realistic, but rather that it is.

Women seem to fare particularly poorly here, as no less than three victims of the book were subjects of rape: abduction leading to rape and murder, asphyxiation after being tied up, gagged, and raped, and rape of a minor by a relative. Even after finishing this title, I can’t decide whether such depictions are exploitative or underscoring an unfortunate reality about female victimization in that era. Among the cases the department instantly dismisses with disdain is a death in an alley of “a longtime fag”. (As opposed to what? A newly minted fag?)

My larger point is that the narrative here, seen through the collective eyes of a group of cops, makes for awfully dispiriting reading. In one well-observed scene, Officer Galeano escorts a woman who just learned her son has died to the morgue for an identification of the body. She speaks numbly to the officer about her lost child’s life and wonders what went wrong; his mind is on meeting his waitress girlfriend when he’s done with the shift. It’s a truthful moment on both sides, and also a depressing one. Just as with a homicide or crime detective, a reader is never able to avoid the reality of an unkind world, and I don’t quite have the talent for benumbed disconnection that Galeano does. There are indeed more muggings and home invasions that end in panicked robbers killing their targets than is comfortable to think about, and knowing that the veneer of individual security can be scraped away by a single gun barrel or masked intruder is not a pleasant reminder.

Some readers, of course, would want to have a shotgun seat to tag along on LAPD investigations, and they will find Appearances of Death an interesting study in law enforcement procedure. (Ironically, they might find the high closed-case rate of Mendoza’s crew a little too fantastic.) It’s my contention that we have such a fascination with serial killer thrillers in our crime novels these days because they offer a bit of the it-will-never-happen-to-me fantastical premise that attracted Golden Age readers. Even when brutally explicit, it is easy to think of a serial killer as an exotic animal, not a commonplace rodent that robs, steals, and accidentally kills innocent people with frightening frequency. We can still convince ourselves that we are out of the destructive path of a serial killer, vicious and rule-breaking as he may be, just as that GAD body in the library is no one we know or need to feel sorry for.

But the steady stream of violence presented in Appearances of Death – from family members, friends, neighbors, acquaintances, and strangers all with base motives of sex or money or instant rage – is frightening in the extreme, because it is constant, random, and very much a part of our world. Forgive me if I prefer to retire to the comforts of the drawing room mystery for a while.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed