Driscoll is pressed into service despite trying to stay off the radar of The Congressman, a politician who oversees an independent counterterrorist group working in the shadows of the U.S. government. The never-surnamed Congressman has raised Driscoll specially to fulfill his destiny as a skilled and lethal agent, which Driscoll resents, along with the fact that the steely older man is also his father. Feeling like a pawn in a game he doesn't want to play, Driscoll nevertheless assembles a small specialist team to help him defeat a Russian criminal named Leo Calvin, who has kidnapped the daughter of a rich industrialist in an attempt to stop production of a new missile system contracted by the Pentagon.

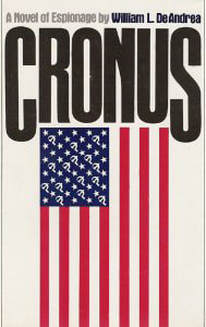

While rescuing Elizabeth Fane and breaking up Calvin's cell is the immediate goal, Driscoll is really driven by the larger objective to uncover a plot that uses the codename Cronus. The Fane kidnapping is one aspect of it, but intercepted messages show that there are many more wheels at work in a larger machine. Research into Greek mythology (in this section DeAndrea warmly acknowledges the writing of Isaac Asimov) tells us that Cronus was a god associated with time – in fact, the Russian plot seems to have been started decades before – and the concept of a father devouring his offspring to keep himself safe. But how do these ideas factor into the bloody events occurring in Draper, Pennsylvania?

With Cronus, William DeAndrea energetically populates his large canvas with colorful characters and explosive moments and events. True to the genre, he can't quite escape the trap that his hero is less charismatic, interesting, and specific than the villains and ambitious achievers he shares the page with. It's never a liability – there are more than enough quirks and foibles in the supporting cast to go around – but it also comes from providing a protagonist who wants to stay a cipher, with no attachments or emotions toward others, lest it creates an exploitable weakness that the enemy could use against him. What I found more distracting is the author's choice to allow multi-character point-of-view within the same scene. It occurs only occasionally, but it's jarring nonetheless. For example, the reader will experience a moment from Driscoll's perspective, but then partway through we leap into fellow agent Miles (no last name)'s head to learn his seasoned view of Driscoll and the situation. Even in the climactic moment, we briefly switch to a villain's perspective, yet not doing that would arguably make the moment more powerful and uniform.

Still, the pacing is good, especially in the second half when the many characters and their backstories have been set up and the plotline can now play itself out. I quite appreciated that the author did not provide comforting assurance of a world where justice is guaranteed to prevail; there are sympathetic characters here who don't make it alive and intact to the final page, and that's worth admiring. When the reveal arrives and the reader learns the details of the Cronus Project, it's a scheme that doesn't really bear close scrutiny (too many variables for one, not least of which being potential defection of agents) but it is dramatic and intriguing, an idea that might have been born from a drink-fueled pitch session between Tennessee Williams and Robert Ludlum.

Cronus is a good read, and one worth revisiting after all these years. The hammock is long gone and the summer cottage has changed owners, but the book would still be a great choice for a lazy weekend of literary escapism. One just needs to forget, of course, that the Russians are now our benign friends with no more plans to infiltrate the United States and sow chaos, according to our current President and the political party that supports him. So breathe easy, America.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed