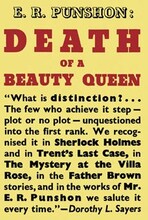

This month the group has chosen Death of a Beauty Queen from 1935, the fifth in an impressive series of 35 Owen books. The premise is immediate and absorbing: manipulative beauty contestant Carrie Mears is found in a manager’s office during a pageant, dying from a stab wound to the throat. The competitor she has tricked into performing poorly – and whose fingerprint is found on a knife – becomes one suspect, while a puritanical city councilor trying to remove his lovestruck son from the premises become two more. The victim’s fiancé arrives soon thereafter on a motorbike, while the stage manager reports that a stranger asking for Carrie but denied entry may have snuck past him in the chaos of ebbing and flowing visitors.

It is true that Sergeant Bobby Owen arrives with energy at the crime scene, but Beauty Queen’s investigation is conducted by Superintendent Mitchell of Scotland Yard. The latter is a very capable figure of authority, and one of my first surprises upon rereading was realizing that the author’s series detective will be more of an observer than a participant in this story. The role change does not diminish the telling at all, as Owen intellectually tries to assess the clues and testimony to solve the case, and the reader is given access to his thoughts and surmises.

Another surprise was being reminded of the novelistic, almost melodramatic approach that Punshon uses, one that often lingers on details and vivid descriptive moments for mood and characterization. It’s another element that connects Punshon with similar detective fiction mood-setters, evocative authors like Gladys Mitchell and John Dickson Carr. I particularly enjoyed the time taken to set the scene from character perspectives, first from the attention-seeking victim-to-be as she soaks in the adoration on the stage and spontaneously sabotages another participant, and then in the next chapter from the harried cinema manager Mr. Sargent, who regrets offering to stage the pageant in the first place.

As admirable (and, for me, as welcome) as such literary flourishes to expose character psychology might be, Punshon’s prose also runs the danger of being excessive and overheated. I think this is why I need to sample this author in moderation; an oppressively rendered atmosphere can sometimes arrest a scene’s energy. In Beauty Queen, for example, we have the very Gothic image of a pious man (the Puritanical councilor) whose hair turns white and who seems to age overnight due to a heavy burden weighing upon his soul:

For a moment or two, Bobby felt too bewildered to speak, nor could he keep his eyes from the brick Paul Irwin had been holding, or his mind from questioning what use it had been meant to serve. Unutterably changed, also, did the old man seem, as if he had passed, in these last few days, from a hale and sound maturity to an extreme old age. And yet, in spite of his bowed form and silvery hair, there was a still a smouldering fire in his eye that seemed as if it yet had power to turn to momentary flame; there was still a hint of power in his bearing, as though all was not yet decay.

There are a handful of colorful clues in Beauty Queen, even as many of them prove to be red herrings. Among them, though, is a potential clue so obvious in its introduction by the author that I was astounded it was not activated or commented upon by the eagle-eyed Bobby Owen! There is so much discussion of the murderer likely having blood on their clothes as a result of a stab to the throat in close proximity, and then the fiancé shows up in Chapter Six with his overcoat covered in mud from a fall from his motorcycle… And yet the highly suspicious garment is never referred to again, either by the author or his detective, nor does it function as a clue genuine or false, except to bewilder or frustrate a reader.

Punshon’s sentences can sometimes run on, as evidenced in the quotation above. But it is helpful to remember that the author actually started his crime story career in 1907, when Victorian-era storytelling defined both pacing and description on the page. So while E.R. Punshon’s writing has been compared with a half dozen Golden Age-era mystery writers already in this review, his work also aligns with the sometimes overdescriptive output of Eden Phillpotts or Anna Katherine Green, and also seems influenced by Charles Dickens and Arthur Conan Doyle. Good company, to be sure, but the contemporary Punshon reader needs to recognize and be responsive to the denser style. I like the extra flourishes, but find they need to be taken in moderation.

Interestingly, the author had already turned 60 years old when he introduced his young policeman in 1933’s Information Received, so the appearance of artifacts from a previous literary era should not be wholly surprising here. Dean Street Press has returned all of the Bobby Owen books to print and has issued eBook editions, and that is cause for celebration. Some of the titles could not be found in their first editions for love or money, and they are worth discovering and reading for any fan interested in between-the-wars mysteries with a Victorian era flavor.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed