Perhaps that pre-judgment is not fair, and I should be more willing to go to whichever galaxies and caprices the writer wants to explore. But I have a much lower threshold for misfiring sci-fi than I do for misguided mystery: whereas I might push through to the end of a whodunit just to see the puzzle resolved, when the plot of a science fiction story makes me disengage, the only space journey that occurs is the book flying across the room.

Frank Herbert, best known for the Dune novels, uses his entry “Murder Will In” to create a locked-room prisoner suspense story unlike anything I’ve read before. His protagonist (and a sympathetic one at that!) is the Tegas/Bacit being, an ego-id dual consciousness that quickly realizes that the death of its host William Bailey demands the leap to a new body in order to survive. But there are certain rules – all science fiction breathes or collapses by its rules – and, as the Tegas/Bacit weakens, its options for staying “alive”, for remaining sentient, begin to evaporate.

A seasoned reader will know within a few pages whether he or she is in the hands of a confident storyteller. Herbert demonstrates his mastery from the start: his pacing is excellent as we understand the perspective and urgency of this ethereal character and its plight; setting and situation are admirably controlled and finite; a poignant sense of claustrophobia is built. Best of all, this science fiction story triumphs because Herbert manages to make the reader care about the “fantastical” character at its core and accept the world, the conflict, and the resolution.

Poul Anderson’s “The Fatal Fulfillment” finds William Bailey using his body-jumping skills in an attempt to identify a perfect ideological society, or at least one with war, disease, and self-involvement under control. While not as artistically daring or dazzling as the two best stories here, Anderson’s tale is a modest success that feels like the conceptual kin to a good Twilight Zone script.

Keith Laumer imbues his Bailey protagonist with such tight-lipped determination to achieve his after-death goal that his story, “Of Death What Dreams”, feels like sci-fi by way of tough guy revenge noir. While Bailey’s plans are known and shown – the process includes obtaining faked identity cards on the black market, undergoing a painful physical transformation, and betting outside the accepted channels of societal gambling – his ultimate motive is hidden from the reader until the final moments. The reveal feels anti-climactic, primarily because the new details don’t feel truly connected to what we’ve followed for dozens of pages. The explanation is unsatisfyingly abstract and removed while the protagonist’s regimen to prepare has been compellingly concrete.

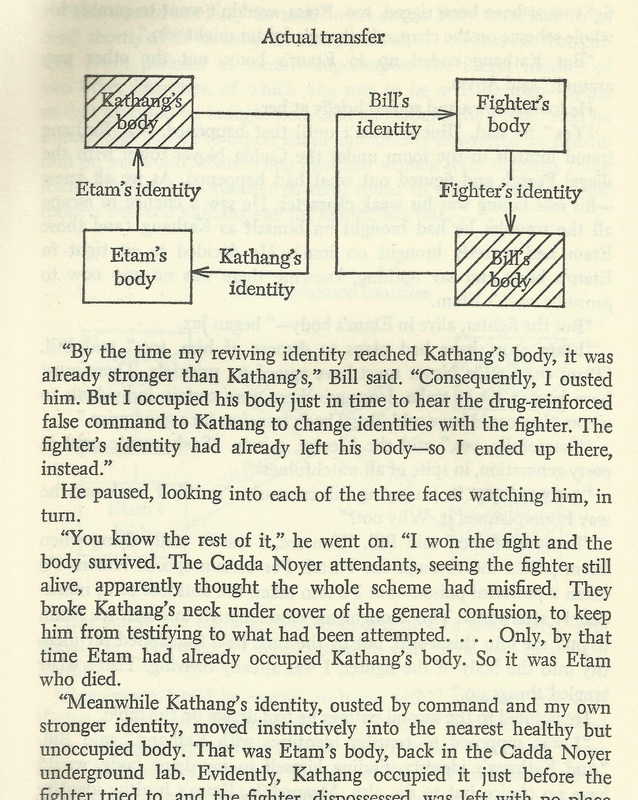

But it is “Maverick” by Gordon R. Dickson that demonstrates how tedious science fiction can become. In this story, Bailey assumes the identity of Kathang, a winged bird-human gladiator who needs to quickly learn the (many uninteresting) rules to survive. With help from the lovely Anvra and advice from the Aerie-Master, Bailey learns that corrupt Electors may be stealing bodies from the Aeries, and that the Caddy Noyer may be involved, and that a portal device has been constructed, and so on.

It’s sci-fi that doesn’t use its fantasy details to deliver anything beyond a very busy plot. As a result, I don’t become engaged because there’s no connection with a truly compelling larger thematic idea. True, there’s an uninspired motif about taking chances, fighting for the right cause, being a “maverick”, but it’s not skillful or unique enough to warrant the investment. This is when, for me, science fiction becomes a chore: there are actually three different diagrams in the story to explain the round-robin of identity transfers between characters, but I don’t know why any reader would care. Just take a look at the clunky prose under the illustration and try to find it even slightly interesting, convincing, or artful.

It is a story filled with intriguing extraterrestrial detail: the bear-like fighter pilot Pinkh, a pawn in the endless Montag-Thil War; a hapless but clever scout cat, doing the dangerous work for its cowardly Filonii masters. Like Frank Herbert, Ellison knows that the rules and the details must be used to explore and illuminate his story’s ideas, not drown or crush them. Bailey’s imprisonment as a soul-for-lease for a galactic merchant becomes an invitation to the reader to ask questions about right and wrong, good and evil, and existence and nothingness. When Ellison resolves his masterful story, it’s cruel and beautiful and immensely satisfying. This story makes me think about my own cosmic path, and see the reality I know as simultaneously expansive and limited. And when a science fiction author allows me to leave his world only to question the one I have returned to, then the genre is gloriously alive.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed