Gold Was Our Grave is the first title I have read by Henry Wade, one of many unjustly neglected writers from Britain’s Golden Age of Detection literature. His detective, Inspector John Poole, was introduced in 1929’s The Duke of York’s Steps, and Wade – the pseudonym of Major Sir Henry Lancelot Aubrey-Fletcher – delivered nearly 20 more mysteries over the following two and a half decades. Gold is one of Wade’s final titles, published in 1954. (I gladly chose it to meet the reading challenge from Past Offences, a great website whose Crimes of the Century invites the community to celebrate mystery and suspense offerings produced during specific years.) This title mixes fair-play detection with an absorbing police procedural format, and succeeds admirably.

In addition to painting an appealing picture of the larger criminal investigation process, Wade also succeeds in populating his puzzle with characters that possess just the right amount of pathos to come alive, but not so much emotional verisimilitude that the genre is jeopardized. At its heart, Gold Was Our Grave is a tragedy, and it is to Wade’s credit that he uses his detective’s formal position to look dispassionately at events, thus avoiding melodrama.

The story: financial speculator Hector Berrenton is involved in a near-fatal car accident, the result of a disconnected steering-track rod and a precipitously sharp turn on the road near his home. The wreck could have been due to the neglect of his disagreeable chauffeur and mechanic, except for the arrival of an anonymous letter posted the day before and addressed to the driver: SAN PODINO. THIS IS YOURS. FALLON NEXT.

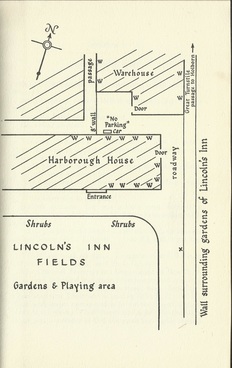

A location map accompanying Henry Wade's Gold Was Our Grave (1954).

A location map accompanying Henry Wade's Gold Was Our Grave (1954). If the latter, the suspect list changes from general to specific, and includes Julian Berrenton, Hector’s son, who may be too accustomed to the good life; Jocelyn Fallon, whose relationship with his business partner may not be as friendly as it looks; ex-secretary Mr. Rightson, who lost his job due to the scandal; and current secretary Daphne Gordon, who appears to be having an affair with the married Fallon.

I greatly enjoyed the capable presentation and assured plotting and pacing of this book; while I am usually not observant enough to arrive at a solution ahead of a Golden Age detective, the pieces fell into place here about halfway through the story. This was satisfying, as Poole then explores the same lines soon afterwards, and even so the author masterfully allows a sliver of doubt to enter Poole’s inner thoughts, planting that wary possibility that the picture may turn once more before all is revealed. There’s a clue in the form of information in the beginning chapters that is hidden in plain sight, and the final explanation is not overly complicated, and indeed benefits from its relative simplicity. It is also affecting that the murderer, when his or her story is told, is perhaps more deserving of sympathy than scorn.

To return to the inner thoughts of Inspector Poole: Wade sometimes allows the reader access to his detective’s mental hesitancies and strategies, and this more intimate narrative perspective adds greatly to the book’s charm. For example, the gesture of a simple civility while interviewing Daphne Gordon in her home fills Poole with regret at his approach:

It would be churlish to refuse, and presently John Poole was enjoying a very drinkable Spanish sherry, sitting in a comfortable chair facing his hostess across the fire. Hostess? That was exactly it; the moment the first glow of comfort coursed through his veins – or whatever it did do – Poole realized that by accepting the drink, and the apology, he had weakened his position; he could not now press his questions as inexorably as he would do to a hostile – a palpably hostile – witness. He had hastily to reconstruct his plan of action.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed