Such unconventionality may not be welcomed by fans of Golden Age Detection puzzles, exactly. In Double Barrel (1964), for example, much of the novel is a dialogue between the inspector and a suspect in the case; with Over the High Side (1971), Van der Valk advances theories about what happened to a patriarch who disappeared from the family boat, but as the members refuse to share their knowledge of the night and incriminate one of their own, a definitive resolution is never stated. And in the story I am reviewing here, 1963's Gun before Butter, the Dutch policeman has several notable interactions with Lucienne Englebert stretching over years – first as a teenager involved in a car crash that kills her father, then in the company of Italian boys arrested during a knife fight, next as a defendant of a theft complaint – before she surfaces as a young woman working as an auto mechanic and marked as a potential suspect in a murder investigation.

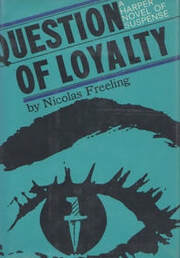

I'm tempted to advise that Nicolas Freeling's writing (like Gladys Mitchell's) may be an acquired taste. His mysteries are very reminiscent of Simenon and his proletariat detective, Inspector Maigret, but they incorporate an even more philosophical tone. As a law officer, Piet Van der Valk is an iconoclast, and indeed a reader should not expect "justice" to be served by having the figure that pulls the trigger or pushes in the knife to be inevitably arrested, tried, and convicted. That isn't the world that Freeling creates – indeed, it's not true of our own reality, then or now – and for me it is a more interesting one because such a world is not bound be the strictures of moral or genre formula.

The Van der Valk novels are not formless, however; they each have narrative and tonal logic that feels highly satisfying (and rather unique) to me. The case progresses, threads are followed, the picture forms. But it's the choices that are made and the worldview of this literate and atypical policeman that make the difference. I have encountered detective characters as outside-the-box thinkers many times, but no sequence has lodged in my memory more than the way Freeling frames a certain scene in Gun before Butter; it has stayed with me for almost 20 years.

In it, Van der Valk wants to question Lucienne Englebert, but she works at a service station in Belgium, where the Dutch detective has no jurisdiction. He tries anyway, and blusters a bit too much to overcome his legal vulnerability. Enter Bernard, the garage owner and an ex-prize fighter, who, after telling Van der Valk to leave with no result, hits him efficiently in the face and escorts him to his car. The policeman leaves the premises, only to drive directly across the road to an unused lot, park, and wait. Eventually, a Belgian patrol officer checks out the parked car, and upon learning that Van der Valk is also police, gives him his blessing to remain as long as he wants. Soon thereafter, a slightly sheepish Bernard crosses the road to ask Van der Valk to return to the station. He accepts, and the two talk about Lucienne (whom Bernard loves unrequitedly) over bottles of Belgian beer.

It's a bravura scene, one of many to be found in Freeling's books, and I'm amazed by it for two reasons. First, it runs completely counter to the expectations of a traditional action crime thriller, and neatly deconstructs its elements. It is a scene of menace and brief violence carried through in a fully understated way; the moment is grounded in the present, but the action is over as soon as it begins. Any other writer would be tempted to stretch a few paragraphs out of the confrontation, with the hero cracking wise and mounting some sort of defense to show his capabilities. Nothing of the sort happens here. Second, the choices all the way down the line – Van der Valk's atypical bluster as overcompensation, Bernard's use of a single punch to get rid of the trespasser, the parking across the road and the guilt-tinged half-apology – are genuinely surprising and yet fully, psychologically sound. It's a sequence that's completely unexpected and deeply satisfying, not least because the action of each person feels so truthful to the character the author has shaped him to be.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed