– Inspector Hardwick, assessing the circumstances in Left-Handed Death

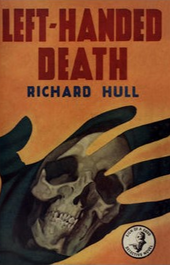

The war years saw a four-year hiatus between Richard Hull’s previous mystery, 1942’s underwhelming The Unfortunate Murderer, and his next tale of office-inspired mayhem, Left-Handed Death. While this book is more engaging than Hull’s prior effort, there are nevertheless some structure and pacing problems on display that will plague many of the author’s later stories. At the book’s start, we find Arthur Shergold and Guy Reeves, managers of an engineering company that manufactures goods ordered through Ministry contracts, deep in discussion. Soon thereafter, Reeves proudly visits Scotland Yard and confesses to strangling Barry Foster, an overweight Ministry accountant assigned to review the company’s finances.

Upon investigation, the police discover Foster dead in his flat, marks on his neck indicating that he was strangled with only a thumb and one finger, which are the digits remaining on Guy Reeves’ left hand after a combat accident in Tunis. But Inspector Hardwick finds the man’s unsolicited confession problematic, and his explanation that he killed Foster because he insulted co-worker and budding love interest Cynthia Trent does not convince. Hardwick tasks his colleagues, Sergeant Matthews and Constable Troughton, with some old-fashioned detective work, and soon alibis are checked, time tables are created, and waiters, bartenders, and bus conductors are shown photographs in hopes of identification.

Curiously, the final 30 pages of Left-Handed Death are to me fleet and satisfying; it is the trek to get there that proves a marathon. Richard Hull seems to embrace the misanthropes of the business world in his books, people who can charitably be considered antiheroes, as Guy Reeves is here. Reeves is vain and egotistical, and if anything, his managing partner Arthur Shergold is even worse. As a result, the reader doesn’t worry overmuch about his plight, even as one suspects he is confessing out of a misguided mix of pride and obtuseness.

Hull’s fascination with despicable characters can yield bracing, wonderful results: visit the egotistical narrator from his début novel, 1934’s The Murder of My Aunt, or the delightfully dyspeptic copy writer Nicholas Latimer in 1936’s Murder Isn’t Easy. But when unlikable characters get paired with poor plotting, as in the desultory Invitation to an Inquest (1950), it is an effort to slog forward. Left-Handed Death finds itself staking out a middle ground. While some dialogue runs and episodic moments are enjoyable – and the trio of nicely sketched police officers, with an assist from an amusing Ministry official named Pennington, steal the show, in my opinion – Guy Reeves remains a weak figure who acts irrationally.

Hull’s structuring of his tale may be the most quixotic aspect, especially as a narrative skeleton definitely exists on which to craft a highly successful story. But that meeting between Shergold and Reeves in the opening pages effectively gives the game away, resulting in an undercutting of mystery and a diminishing of suspense. For some reason I don’t understand, Hull also has Reeves send a letter to Cynthia Trent boasting of his impending cleverness before he goes along to Scotland Yard to confess. Why does he do it? What will that help? I’m not sure. Nor does Richard Hull do much with that message, beyond having Inspector Hardwick note the letter’s postmarked date and time. That, along with the strange circumstances and inner motives that inspire Reeves to confess, add to the list of elements that alienate more than intrigue.

For those who wish to sample this interesting but uneven experiment in crime fiction, Agora Books has returned it to print in trade paperback and eBook editions. For a second opinion, you can find reviews at crossexaminingcrime, In Search of the Classic Mystery Novel, and Martin Edwards’ Crime Writing Blog.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed