Further, the character views and motivations are also of their time, and could understandably sour on a reader when tastes and social norms reflecting attitudes 60 years later are applied. Most problematic in this aspect is the persona of the victim, who comes to life in flashback as an attractive but manipulative man-eater, a woman who leaves her husband and children for Martin and then disposes of him in turn, taking pleasure in the power she wields. Inspector Van der Valk (here and in other stories) does not fail to appreciate the well-shaped leg or firm form of a secretary or housewife, and the detective's intelligent, anchored wife Arlette is not yet on the page in Amsterdam, only referenced, so Martin's clear-eyed and understanding girlfriend Sophia must provide the book with its check against casual chauvinism.

Inspector Van der Valk will quickly become a memorable, likeably unostentatious lead for the series, solidifying fully in the third book, 1963's Gun Before Butter. But in Amsterdam, we are still watching the brushstrokes being applied. In some early scenes, Van der Valk employs a coarseness or jocularity that might be a tactic to get his suspect to drop his guard, but comes off as against type to the introspective detective we know from future stories. The inspector's willingness to sympathize with the accused, however, as well as his penchant for carting Martin over to the crime scene and frankly discussing the case with him, are habits that will remain and expand. Van der Valk's quiet but mischievous contempt for the self-importance and bluster of bureaucratic figureheads within the Dutch justice system is also in place already; this little-cog-in-a-cumbersome-machine perspective is one of the most winning qualities of Freeling's novels.

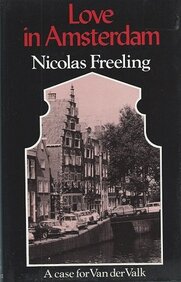

When it is compared with the other books in the Van der Valk series, Love in Amsterdam suffers a bit. Future stories will filter their characters and crimes through the inspector's humanist point of view, but in this one we see the world from the suspect's perspective. The choice should make the narrative more immediate, with the stakes higher, but it doesn't quite do so. Nicolas Freeling provides Martin with such an equable personality – not very much seems to surprise or trouble him – that it's hard to feel one's own pulse rise in proxy to the situation; we are as distant and removed from the action as the nominal protagonist seems to be.

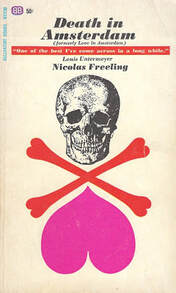

The book was released in the U.S. the same year as Death in Amsterdam.

The book was released in the U.S. the same year as Death in Amsterdam. Tracy over at Bitter Tea and Mystery reviewed Love (or, as published in the U.S., Death) in Amsterdam last year. I hope she and others continue to explore the Van der Valk series, as I look forward to reading each title again after nearly two decades since my initial visit.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed