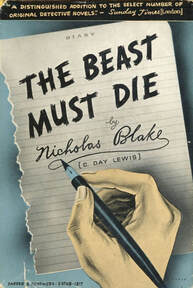

I'm working my way through Nicholas Blake's Nigel Strangeways mystery series after having first read the books nearly 20 years ago. But this month, when I came to the excellent 1938 entry The Beast Must Die, I was reluctant to revisit it. Two reasons for this: the central premise is so vividly designed and presented that I still felt familiar with the story after all these years; and I had such a good experience the first time around that I didn't want to try it again merely to find diminishing returns.

Happily, this Beast holds up and well warrants a second look. And for mystery fans who haven't yet read the suspenseful, twisty novel, there's even more to enjoy.

It is when Cairnes insinuates himself into Rattery's circle and begins the game of cat and mouse that The Beast Must Die becomes an irresistible, page-turning tale of suspense. A murder occurs – we have been witness to Cairnes' inner thoughts and deadly plans throughout the diary's narrative – but not in the way that intended killer or intended victim expect. Nigel Strangeways is brought into the dramatic affair, and he finds a number of well-drawn characters to view as suspects, including Rattery's dour, manipulative mother, his ex-mistress who has begun to fall for Frank Cairnes, and even Rattery's bullied and emotionally fragile teenage son.

I admire author Blake/Day-Lewis's skill here to shift and blend many distinct elements of the crime story, from traditional whodunit and detection to Shakespeare-inspired cold revenge tale to a human-sized moment of modern-day tragedy. The various tones not only fit together well but also keep the story propelling forward with a what's-next urgency that later Blake novels often don't deliver. Blake's early titles are filled with clue- and character-generated attention to detail, and it is clear that he is taking seriously the challenge of crafting a satisfying fair-play mystery. Like many good writers with a similar pedigree, he may be traveling in a popular genre but he's not taking a condescending view. The moods, brooding natural settings, and pathos that are generated (interestingly, both at the beginning and very end of the story) prove highly effective, and hint at Day-Lewis’s talents as a poet who is attentive to imagery, structure, and specifics.

Even if one still finds some flaws in this Beast – there are a couple expedient coincidences for one thing, and the murderer’s rationale that inspires the commission of that crime at that moment could be viewed as either bold or foolhardy – it is still a very engaging read. Other reviews of the book can be found from Kate at crossexaminingcrime (also a reread for her, and equally good the second time around), Nick at The Grandest Game in the World, and The Puzzle Doctor at In Search of the Classic Mystery Novel.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed