Every story here resolves with a "happy" ending, i.e., the criminals are caught and justice is served. The locale can be metropolitan, but more often the authors set their crime stories in America's underpopulated heartland, and some dramas play out in secluded cabins in the woods while others take to the prairie, exploring cowboy culture and frontier codes of ethics.

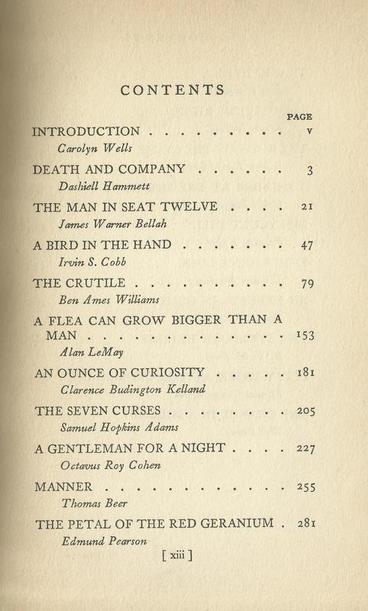

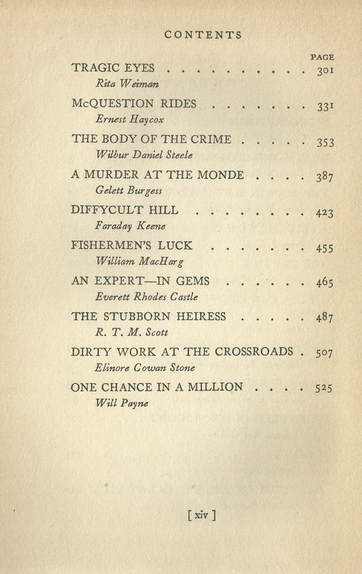

Because the book is a relative rarity, I share the list of stories and authors here. One item worth noting is the length of these stories; many average about 30 pages, which feels a little long in several cases. Only a few merit their extra word count, and a couple, like "A Murder at the Monde" by Gelett Burgess, let the reader get well ahead of the story, and one is left waiting for a resolution.

"The Sherlock Holmes type grew so popular as to become trite, and has been rather obscured by the clear-thinking, slow-moving sort of investigator, whose common sense and general information stand him in good stead when brilliant imagination fails."

Wells' perspective sounds at times fairly dismissive of the value of mystery fiction:

"What is the mystery story? To entertain and to interest, to amuse. It has no deeper intent, no more subtle raison d'être than to give pleasure to readers."

Still, she admits to a practical mental use:

"Many of us are very apt to suffer from mental cobwebs, and there is nothing equal to the solving of puzzles and problems for sweeping them away."

For example, no less than four stories incorporate the scenario of a captive or compromised protagonist sending a coded message to the outside world, and one which needs to be interpreted correctly by outsiders in order for help to arrive.

Females seducing males in an attempt to steal jewels or obtain money is another favorite storyline here. "An Expert—In Gems" by Everett Rhodes Castle follows a predictable pattern of attempted theft and tables turned, while Rita Weiman's "Tragic Eyes" takes a more interesting path, as a femme fatale tries to put a sympathetic U.S. Senator (are there any of those left?) into a position of blackmail, only to be foiled by the congressman's acumen and intelligence (I ask the same question again). "The Stubborn Heiress" by R.T.M. Scott offers a male golddigger – here, an ersatz nobleman – and the (male) detective must convince a smitten woman that the imposter's intentions are less than honorable.

Every author has a unique writing style and storytelling manner, and in a couple tales that authorial voice manages to get in the way. "The Man in Seat Twelve" by James Warner Bellah is one such example, as the story is both overlong and filled with hasty sketches for scenes and characters with no definition. I still don't know what to make of "Manner" by Thomas Beer, an odd story of a businessman who is either proud of or ashamed of his son, who seems to be autistic. I think the son, Lion, solves a crime by accident, but I'm not certain.

More entertainingly, Samuel Hopkins Adams takes the overstuffed approach to tell the fevered story of "The Seven Curses": a car accident victim drags himself to the bushes of a haunted house, and then watches a trio of robbers try to break in only for two of them to die an agonizing death. Fortunately, the wounded man shares a hospital room with the third robber, and the strange truth comes out. "The Seven Curses" has a Grand Guignol energy that's appealing, and Adams shows a penchant for clever clueing, but it's all a bit breathless and hard to believe.

What a sight it was for the evening sun to see, level and bloody rose beneath the eaves of the chestnuts! Dan Kinsman, bemused, commencing words and swallowing their ends on half-choked chuckles, even as his eyes, quick for once, kept slant track of Vivian's every oddly exuberant gesture. Daniel, beatified, accepting wonders with a new omnivorous trust. And Vivian Kinsman, unbelievable, a princess freed from some evil enchantment in exile, returned to her kingdom, leading them.

"Body" involves a boy, Daniel of the newfound omnivorous trust, who views his father differently after his mother dies. Daniel can remember a traumatic experience that occurred involving his father when he was three years old, but he cannot recall the details. So he returns to his childhood home and begins a sort of vision quest, depriving himself of food and water and sleep until his mind will unlock the closed door guarding that memory. It's a gripping story with a satisfying dénouement, and it also speaks to the precarious relationship of fathers and sons, and of lies told out of love that inevitably harm. But the writer's baroque tone makes the story much less accessible than it should be.

I'll conclude by mentioning two of the strongest stories in this collection, and coincidentally they are both grounded in American Western culture. I am not especially a fan of the Western genre, but like any genre there is always the opportunity to use its elements to tell a successful and engaging story. "McQuestion Rides" by Ernest Haycox finds a sheriff visiting a ranch house as he tries to find a killer whose identity is unknown. The storytelling here is swift and sharp, and there's a very satisfying human observational component.

And "An Ounce of Curiosity" is one of several stories that constant journal contributor Clarence Budington Kelland would write featuring the sardonic frontiersman Scattergood Baines. While the psychology of the tale is rather simplistic – along the lines of a sadist to animals must be the killer – Kelland's wry American humor shines through on every page. Here's a sampling, where the elderly detective deflates an excited vigilante who has likely been chasing the wrong suspect in a robbery:

"How d'ye know this feller you're chasin' done the deed?"

"Sanford said it was him."

"Recognize him plain, eh?"

"The feller was wearin' a red handkerchief over his face."

"Knew him by a strawberry mark, mebbe?"

"No, but he said it was him. And folks seen him a-comin' down Sanford's lane."

"With the pliers [the assault weapon] into his hand?" suggested Scattergood.

"Didn't have no pliers, but he was a-runnin'."

"With thutty-eight hundred dollars in his hand?" said Scattergood.

For me, many of the stories here were worth reading, and the anthology provides some insight into the themes and values of popular mystery fiction in 1930s America. I'm always grateful to read work from forgotten authors, and in some instances – such as with Clarence Budington Kelland and even with the frustrating Wilbur Daniel Steele –the cobwebby stories encourage some rigorous dusting and a call for further investigation.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed