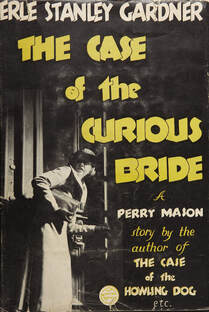

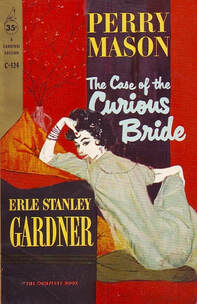

One of three Perry Mason novels published in 1934, The Case of the Curious Bride has me once again in awe of Erle Stanley Gardner’s abilities. As with the other Mason stories I have sampled, the author delivers a complicated (and at times breathless) plotline so his attorney protagonist can dazzle readers and prosecuting counsel with some tricky – and ethically if not legally questionable – slight of hand. The genius of Gardner’s books lies in the way he shapes his plot specifics to give Perry Mason an opportunity to use these elements as ammunition in court. The actions and events by multiple parties leading up to the moment of the crime are rarely believable; there are far too many coincidences and conveniences for the setup to feel realistic. In Curious Bride, for example, we have a 2:00 am apartment assignation with a blackmailer where no less than three separate visitors with motives are present, and a pair of neighbors on hand to provide an earwitness account of the exact moment of murder.

And yet this busy scrimmage is a prelude to the clever manipulations that follow. Objects that other mystery writers would treat as clues Gardner lets Mason rotate and use as evidence for the defense, but only when the lawyer puts them in the context he needs. Here, such tactile and workaday items as doorbells, spare tires, and garage doors are used to challenge the uncertainty of witnesses and exonerate the defendant. This is one of the great charms of the Perry Mason books: we watch as the lawyer first learns about the object and then employs it in a surprising way to help clear his client.

Rhoda Lorton’s perilous situation turns on a question of legal union status: is her marriage to wealthy second husband Carl Montaine annulled if she is still married to her first? Yes, and prosecutor John Lucas needs that annulment completed so the no-longer-married Montaine can then be forced to give evidence against the woman who is no longer his wife. Carl’s imperious father, who believes Rhoda is not deserving of the family name or fortune, presses for the annulment, but if Perry Mason can prove that Rhoda’s first marriage was illegitimate, then the Lorton-Montaine union would stand. Twists and complications abound, and while it’s unlikely that anything so convoluted would come along in reality, on the page and in Gardner’s hands these legal finer points become the basis for wonderfully escapist entertainment.

It is easy to praise the plotting mechanics and inspired use of legal code in the Perry Mason books, in part because they are so exuberant and give each story a delicious “what comes next?” forward momentum. But this reader also can’t quite overlook Gardner’s transgressions as a prose writer. Once more, dialogue identifiers are overused mercilessly. Two-character exchanges are filled with “asked Perry Mason” and “said Paul Drake” when we know exactly who is speaking, especially since so much dialogue takes the form of Mason asking a question and the other person answering. Used sparingly, identifier phrases are innocuous and helpful; overused in a Mason novel, they are repetitive and redundant.

I also get a little restless with Gardner’s use of adverbs, and each time Mason or the judge looks at someone “frowningly”, I react wincingly at the awkward word choice. And there’s a curiously complete newspaper account providing details of the murder, which is quoted in full in the story. And by complete, I mean complete: the paper readers (and Mason) learn that there were no fingerprints on the fireplace poker and that a set of keys were found at the crime scene, with a photographic reproduction of the keys prominently featured on Page Seven. Have the police held nothing back? Or perhaps the cub reporter is also moonlighting as a crime scene investigator for the city. Minor distractions, but ones that still offer unfortunate little bumps while traveling along an otherwise brilliant road.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed