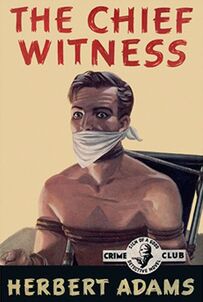

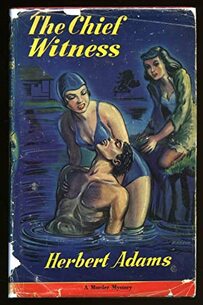

Such criticism and unflattering comparison may make one conclude that I am anti-Adams. But I am not at all; it is simply difficult to be passionately pro-. The Chief Witness from 1940 is my second sampled book from this author (after 1936’s A Word of Six Letters), and I will likely go on to read more. Like dozens of other Golden Age writers who busily published mystery fiction for decades and are largely forgotten today, Herbert Adams’s flaw is likely that his stories aren’t distinctive enough to be memorable. They have decent plots and pacing, the characters are agreeably drawn, and there is a dispassionate investment generated in the reader to see how everything shakes out. But it is damning with faint praise, I fear. I enjoyed The Chief Witness; the problem is that I didn’t enjoy it nearly as much as my last Agatha Christie or Rex Stout, or even as much as my last Crofts or Rhode story.

Witness has an intriguing set-up: two brothers die on the same evening, almost at the same time, in their respective homes. Both appear to have shot themselves with a revolver, and both are in rooms where a smashed timepiece hints at the time of death. As Roger Bennion follows Inspector Goff around on his investigation, he learns that the details don’t quite add up for a double suicide verdict. Each man has a possible enemy or two who would like to see either Alexander or Frederick Curtis dispatched, but no one appears to have a strong enough motive for killing both brothers. And if murder, then why the choice for one hand to dispatch both men on the same night, a move calculated to arouse suspicion?

Bennion (and the reader) soon discovers that there are male suspects who might be unscrupulous enough to kill and female ones who are emotionally tied to the victims. To his credit, Adams excels at presenting sympathetic, larger-than-life female characters that evoke a response in the reader. One example is Margot Watney, a commanding young woman whose argumentative attitude masks a vulnerable fear that her fiancé, Wilfrid Mounsey, may be arrested for the crimes. Another beguiling woman is Alexander Curtis’s wife, Helen, who was never legally married and is now fighting with her stepdaughter Delia for control of the estate. While these women characters will never be confused for fully rendered creations, they do resonate in the book to a much greater degree than their male counterparts, who are heroically dull or villainously melodramatic as called for.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed