“How, in the name of all the gods at once, do you imagine that you are going to avoid detection? When Monty – or if you insist, if Monty – is found full of nicotine, it must be you, and there’s enough written evidence in your own handwriting to hang you for a certainty. The trial will be a pure formality. Similarly, if Monty is found with his beastly sword-stick stuck into him, the intelligent sleuth collects me – or Prunes, if it turns out to be a revolver with which the trick has been done.”

“Does he? You know, I think that you underrate the intelligence of the average sleuth. The first thing that he will say to himself is that if I was really going to do it, the last thing that I should actually use would be nicotine. Therefore, he will say to himself: ‘it can’t be that charming fellow Bethel, whom anyhow I should very much dislike to cause to be hanged.’ Similarly, if the sword has been used, he will say: ‘it can’t be that red-headed, bad-tempered blundering ass, Wrangham, richly though he deserves a hanging.’ That’s how he will argue.”

“But that implies that each of us might do it in such a way as to throw suspicion on one of the others.”

“Precisely. Three people, three ways. That gives Monty nine deaths in all, like a cat.”

Arthur Bethel takes great pleasure in extracting nicotine from a pack of cigarettes to be offered in capsule form. Norman Wrangham prepares a sword-stick and P.R. Unwin-Shackleton – or “Prunes” to Delia Martindale, his presumed beloved – acquires blank cartridges to use in Monty’s desk-drawer revolver. The evening of mock-execution does not go entirely as planned, however. Kernside summons the police, explaining that he arrived eight minutes late to find that one or more people decided to make the company a success. Detective-Inspector Fenby investigates to find a strange scene: Monty has a sword-stick through his heart, a bullet in his head, and (as medical consultant Doctor Lovell reports) three undigested capsules in his stomach.

The three previous visitors all claim to have left their victim in good health after their encounter, but doubts begin to creep in. Bethel admits to planting a false moustache around the hilt of the sword-stick – which might have contributed to an accident – while Wrangham can’t remember whether the sword was sheathed when he stabbed out in a bit of play-acting. Prunes, meanwhile, is not certain whether he unloaded the cylinder in the correct rotation when substituting the two blanks before firing. Clues to motive (beyond the shared dislike of a boring individual) are scarce, but Fenby pursues two: did Monty’s interest in Delia spur the phlegmatic Prunes into a jealous rage? And to whom or to what does the scrap of hurried handwriting with either “ABetc” or “ABitl” refer? Was the literal overkill the doings of one man or the work of a cabal? Fenby finds the answer and acts, thus concluding the business of The Murderers of Monty, Limited.

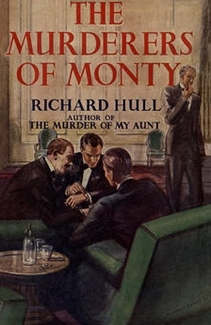

Review: It is clear that Richard Hull was attracted to the Mystery Story with the Enticing Premise, a plot element – a cynic might say a “gimmick” – that immediately generates interest. And that is all to the good, since it attracts Golden Age Detection readers like me to choose such stories with a unique approach, such as offering the last chapter first (in Last First, naturally) or providing diary-entry narration of a hopeful heir plotting murder (in The Murder of My Aunt). But the Enticing Premise also comes with a Potential Pitfall: the story needs to sustain itself and satisfy the reader beyond its clever setup. And this is where 1937’s The Murderers of Monty and some of Hull’s other mysteries get mired.

Monty is still an enjoyable read, and the light tone and comic perspective remain intact; Hull’s prose and dialogue remind me agreeably of Anthony Berkeley’s books or the earliest Nigel Strangeways stories from Nicholas Blake. Here, the lopsided courtship between the strong-minded Delia Martindale and the vacillating P.R. Unwin-Shackleton provides moments of dry social humor, while the friendly sparring between Detective-Inspector Fenby and his contrarian colleague Doctor Lovell seems right when discussing a crime with too many variables. In part, though, it’s the author’s admirable adherence to fair-play plotting that allows the reader to identify the killer 40 pages before Fenby does.

One difficulty to surmount with this particular Enticing Premise is tied to the timetable: if the victim is killed by gun, sword, and poison, and if each participant visits in the arranged sequence, a single killer will by necessity have to administer the death blows after the others have come and gone. If not, the next person arriving will notice the unresponsive victim and, with no reason for an innocent man to lie, would explain his findings to the police. With the final visitor arriving late for his meeting – and why is Kernside allowed to not commit to a murder method? – the killer must have revisited within that window of time, unless he was the last person scheduled to arrive, i.e., Kernside. This between-the-penultimate-and-the-final window for the crime makes the confusion over witnesses’ statements unsatisfying: either the innocent person left Monty alive and breathing (and knew that he did so) or not. Uncertainty over shooting and stabbing, and its effects on the recipient, strains credulity, even in a work of light detective fiction.

Connected with this fair-play flaw is another: one piece of information that defines motive and identifies the murderer is easy to spot, despite Hull’s masking of the piece’s significance until the tale’s climax. This makes the book’s procedural middle chapters slow-going until Fenby catches up with the reader. (I should admit that, while I am an avid reader of mystery stories, I am not particularly adept at spotting who “done” it, and lazily wait for the detective to unmask the culprit. For this reason, when I am ahead of a fair-play mystery story, it is fair to assume that others will be as well.)

One senses a missed opportunity too among the quartet of suspects, whose corporate attempt at gallows humor – principally the work of the over-imaginative Arthur Bethel – has now made them suspects in a murder investigation. It would be genuinely interesting to see these company members grow suspicious of one another, with subsequent collusions and betrayals bringing out the ugly side of human nature. This would invite the reader to doubt each suspect in turn, keeping Fenby engaged and the characters scheming to save their own skins. Instead, Hull has his men remain polite, slightly concerned, and curiously uninterested about which close colleague might be a murderer in their midst.

And speaking of unconvincing character traits, it is surprising that the victim, who, we are told, is insufferable and worthy of murder several times over, is quite benign and amiable. We learn that he has hair on his ears and that everyone, Delia included, finds him an incredible bore, yet the limited stage time Hull provides Monty doesn’t demonstrate that he is any more pedantic or irritating than the personalities of the founders of The Murderers of Monty, Limited. While I would be happy to consider this an intended irony on the author’s part – that the murderers are more deserving of elimination than the victim – such evidence is lacking to attach a larger social comment to the choice. For a book that is also benign and amiable, The Murderers of Monty is somewhat done in by an ambitious scheme that aims higher and falls shorter than its premise and its characters can deliver.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed