Indeed, Nigel has his hands full analyzing O'Brien's guests and learning their histories with the ex-airman. Uncharacteristically, the detective (and others) sleeps through the night's events, and Strangeways wakes only to discover O'Brien dead in a hut separated from the main house.

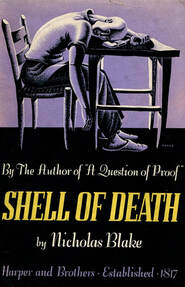

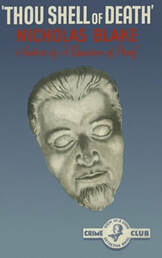

Thou Shell of Death is great fun for classic mystery fiction fans, since it delivers on multiple counts: it is a sneaky fair-play puzzle with all of the clues and character psychologies offered up to the reader to organize and theorize about; it is spiritedly written and often quite humorous in description and design; the suspects are distinct personalities and used within the plot to good effect; and Blake (the pen-name for poet Cecil Day-Lewis) seems to be more comfortably familiar with his protagonist here than in his previous title, A Question of Proof. The character is now less of an eccentric for the sake of color – we learn in Proof that Strangeways has to sleep under a weight of bedcovers and must constantly drink tea, quirks that are thankfully not stressed here – and instead is a man intrigued foremost by people and their motivations and mannerisms. it's a better choice and it gives Nigel some humanity, while at the same time defining him not by his quirks but rather by his intellect.

Another aspect of Thou Shell I greatly enjoy is the author's handling of the fateful backstory that explains, among other things, O'Brien's wartime recklessness in combat, the murderer's relationship to the victim, and the body count resulting from that holiday house party. The way I view it, a mystery writer can use one of three general approaches to give the reader information about Past Events that tie directly to present deeds: 1) the detective can reveal the connection and explain the significance during the iconic end-of-chapter dénouement; 2) the author can dramatize the Past Event in separate chapter sections, with the reader understanding the significance toward the end; 3) the detective (and the reader) can learn details through interviews of witnesses or contemporaries as the story progresses.

This also made me reflect on my frequent dissatisfaction with Approach #1, wherein the detective reveals the Past Event at the conclusion of the mystery story. It often feels to me as a narrative opportunity missed, as the result runs counter to the fundamental writing maxim of "Show, don't Tell." The reader may be surprised at the revelation, but he or she is largely denied the emotional catharsis (or generation of empathy) that might occur if one is invited to experience the event via flashback or retelling.

He reminded me – for which I'm very grateful – that Agatha Christie was a constantly experimenting and creative structurist who varied her methods to meet her story needs. I feel that her classic 1939 tale And Then There Were None is profoundly resonant in part because some of her characters are haunted by and are reliving these past moments, and because Christie allows us to access some of those memories, most notably with Vera Claythorne. While some titles do deliver the Past Event as a drawingroom surprise, many others use tragic previous events to great dramatic effect as Christie concentrates on how the past ensnares and envelops those who are unable to break free. Ordeal by Innocence (1958) and Cards on the Table (1936) are just two examples that explore this past/present frisson, while 1943's Five Little Pigs (whose alternate title, appropriately, is Murder in Retrospect) is a particular favorite of Brad's, with the author using the specter of family tragedy to haunt the lives of their now-adult characters decades later.

The discussion was a fruitful and informative one, and I'm thrilled to see that Brad has decided to share his thoughts on the intersection of past and present in Christie's work in this excellent blog entry.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed