The eccentric matron of the house, an object-dropping, exclamation-stating lady of older middle age named Yvonne de Belmont, has decided to employ a companion to help her in the afternoons. Ever the contrarian, she sets her sights on Clara Fison, a young woman whose last employer (also an elderly lady) met her death under suspicious circumstances.

Mrs. de Belmont’s doctor, a plummy Scot named Holmes, may be a little too eager to see her prized stamp collection – was his presentation of an obviously forged St. Lucia stamp a pretext to gain access to her books? – and, shortly thereafter, indeed a valuable postal sheet goes missing. There is also a saturnine accountant named Sumner, tasked with maintaining the ledgers for the wine merchant service begun by Yvonne de Belmont’s late husband. There appears to be irregularities with the accounts, and Sumner is not at all happy that the widow sends Clara Fison to ask some pointed questions about the profit margins.

17A Elizabeth Square has a poorly lit foyer with a double staircase leading to the rooms, and it is in this limbo location where one hapless person falls into a trap that leaves the body suspended from a rope hung through an obscured skylight. Detective Inspector Oliver approaches the strange case with an optimistic demeanor, but soon has questions. Was the victim the intended target of murder? Who placed the sweeper against the skylight pane, making the already dark foyer even more difficult to navigate? Who rang the doorbell that summoned a person to their doom? Oliver sorts out the merely eccentric from the lethally inclined, and it is now up to Ambrose Gray, Junior Counsel for the Prosecution, to deliver a verdict of guilty.

Review: The elements that are working well in this later mystery by Richard Hull tend to be the ones for which he has exceled in the past. Once again, we have a somewhat unconventional framing device, as we are given some details from a junior barrister’s point of view, but other critical information is withheld until we get into the plot proper. It’s a tactic that’s not necessary, but it does help slightly in terms of novelty of approach.

For me, it is the dark humor with which the frustrated cast of characters is drawn that holds the most appeal. Mrs. de Belmont is a great minor creation, as she speaks her inner monologue deliberately and directly aloud, a trait that either amuses or alienates her hearers, depending on their familiarity with the crafty woman. Likewise, a detail such as her dropping of items is both comical and psychological, as it is clear that she respects those (like Clara Fison) who don’t rush in to collect the test objects and come to her aid, and despises those (like her nephew) who do. The other characters are provided with enough backstory and peculiar mindsets or motives that the plot is nicely populated with suspects until the murder occurs – which is halfway through the novel, not counting Ambrose Gray’s framing scenes.

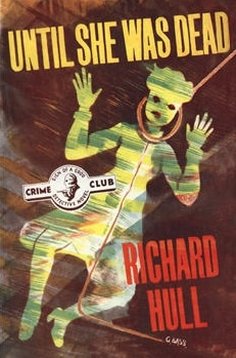

The mystery puzzle at the center, and specifically the booby trap method of murder, don’t deliver the same satisfaction, unfortunately. This is the eighth Richard Hull title I have read since first encountering his debut, 1934’s The Murder of My Aunt, and it is easily the most desultory. Somehow – perhaps because of the delayed pacing of the inevitable murder – the many dialogue scenes between characters never really engaged me. There is a lot of talk about wills and stamps and wine sales, and while the characters individually (and their ulterior motives) are interesting, the discussions sometimes were circular and stagnant. I did not have difficulty finishing Until She Was Dead, but the conversational scenes were met with growing impatience as I moved through the book.

As a reader, I am a happy suspender of disbelief when it involves Golden Age mystery stories and their often fantastical plots, but the planned murder method Hull describes here left me skeptical to say the least. The killer chooses to rig a noose near the top of a flight of stairs, and the plan is dependent on the victim tripping on a run of florist’s bass twine so that his or her head slips into the noose, and then the body manages to swing over the banister into the void between twin staircases. Hmm. I kept expecting the sheer impracticality of such a one-two-three process to be a clue in itself, such as that the victim needed to be drugged or strangled in the first place so that he/she could be maneuvered into this set of circumstances. The odds feel rather 20 to one against, and how are you guaranteed to snare the right prey?

Until She Was Dead is a mixed affair: enjoyable characters, less enjoyable conversations, and an unbelievable murder method contribute to an uneven reading experience. Many thanks to the very nice librarians at Kent State University who provided access to the text of this difficult-to-find title for academic purposes.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed