ON (Protracted) DISCUSSION AND DETECTION

It's very interesting to hear how readers interpreted Gladys Mitchell's switch from Butcher Shop's earlier busy plotting to Mrs. Bradley's conversational speculating, notably in Chapter 20's "The Story of a Crime". The consensus is that all that after-the-fact discussion doesn't help tempo or tone. Kate from crossexaminingcrime reports that she "rapidly lost interest in the book in its final third… There was a lack of new information and the narrative revolved around protracted discussion, which went over familiar ground."

Martyn Hobbs expands on this tactical change: "The comic theatrical energy of the previous acts somehow dissipates to be replaced by the static theatre of conversation. The sad surprise of these last chapters (and it is interesting how the novel falls into the neat divisions we have followed in this reading group) is their uniformity of style and tone. As the endless scenarios are rehearsed of that fateful night and the subsequent dismembering of the unfortunate Rupert, my interest at least flagged."

Personally, I can certainly see how the gear-change from action to theorizing can feel like an unwanted change of pace, especially here: farce doesn't usually give over its final climactic minutes to ruminative conversation. But it's part of what the puzzle mystery convention calls for, or at least encourages. Of course, Agatha Christie was expert at this expository high point, with Poirot going around the room of suspects and cancelling each out until he arrives at the one who done it. Here, Mrs. Bradley isn't really confronting suspects but vocalizing her thoughts to those caught up in the crime. It's not the "j'accuse" moment but rather another set-piece where Mrs. B gets to speak and act in ways that will endear or unsettle her audience. But it's also a necessary element, where the reader gains access to the eccentric detective's thinking process.

ON THE NOTEBOOK

J.F. Norris of Pretty Sinister Books comments, "We are given a chance to peek into the pages of her notebook, a regular feature of the Mitchell mysteries in her early years, but soon dispensed with after Death at the Opera, I think. Here she outlines and stresses the odd incidents and seemingly random nature of the various mysteries as well as cleverly throwing several red herrings into the batch."

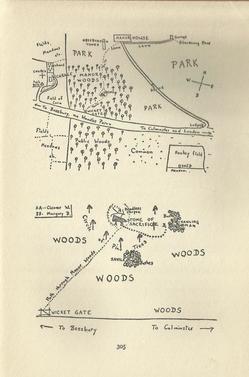

The Note-book entry also contains a hand-drawn map (likely created by GM herself) to help readers understand how sight-lines might obscure a headless body behind the Stone of Sacrifice for some of the woodland visitors, and to make general sense of that very busy evening.

ON MRS. BRADLEY ONCE MORE

PERSONA

Readers cannot escape the spirited, opinionated personality of Gladys Mitchell's memorable detective, although fortunately we are not physically near enough to receive a bony-fingered poke in the ribs. Contributors continue to talk about Mrs. Bradley's extreme appearance, her unorthodox approach to morality and justice, and her (and her creator's) affinity for young people.

Mystery writer Catherine Dilts, who has encountered Mrs. Bradley for the first time with this book, observes: "I have been disturbed by the awful physical descriptions of the amateur sleuth. In Chapter 24, even she describes herself in unfavorable terms. She gazes at herself in a mirror, observing 'her unpleasing reflection.' Mrs. Bradley has a grin described as hideous, a hand that is 'a yellow claw', an expression at one point like a 'cruel beast of prey', she peers 'hideously', and her most flattering physical description is [of being] birdlike. I kept wondering why Mitchell would treat her main character so harshly, until it finally struck me. The Mystery of a Butcher’s Shop is described as a send-up of Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple series. I suggest that Mrs. Bradley also mirrors classic British heroines such as the homely Jane Eyre and Jane Austen’s numerous plain heroines. Mitchell just kicks it up several notches."

There is no doubt that Butcher's Shop is meant as a parody of the tropes of popular detective fiction, which was in its British hey-day in 1929 and would burn brightly for another decade or more. (Agatha Christie would debut her unassuming octogenarian detective Jane Marple in The Murder in the Vicarage one year later, in 1930, but Catherine's comment holds true, as amateur sleuths are supposed to be charming and identifiable, not screeching and off-putting.)

PERSPECTIVE

I want to tread lightly here, as the psycho-analyst's unconventional view of the world – specifically regarding morality and justice – is closely tied to her decision of how to deal with the guilty party at the end of the book. Trying to minimize spoilers, I can report the following comments from readers.

Kate and others note this striking line of Mrs. Bradley dialogue, from Chapter 19:

'That is the worst of a crime like murder. One’s sympathies are so often with the murderer. One can see so many reasons why the murdered person was – well, murdered. The chief fault I have to find with most murderers is that they lack a sense of humour.'

Catherine also refers to the quote above. 'That is the worst of a crime like murder. One’s sympathies are so often with the murderer.' With this remarkable statement, Mrs. Bradley illustrates what is a common theme in cozy murder mysteries to this day. The victim is often a person who was such a wretch, he or she deserved to die. The point of finding the killer is often to clear an innocent suspect accused by the police."

Joyka calls Butcher Shop's final chapters "one of Mrs. Bradley’s neater solutions. She keeps stressing the tidiness of the murderer and the tidiness of [one specific character] but no one seems to put it together but her. Even though I have read this book before, I still had to search for all the clues right up to the end. And as usual, no one is hanged; there is a gentle final solution for all. But what in the world are a cellular vest and trunk drawers?"

PANTS

And as the subject has been introduced, allow me to share J.F. Norris's frustration – and eventual reconciliation – with the Clue of the Omnipresent Trousers:

PEOPLE (the Young Ones)

Even an affinity for her younger characters doesn't mean that they will necessarily stay in the spotlight, however. From Martyn: "Another slight disappointment was the fading out of Felicity, who had been such a fresh attractive presence, after she took offence at Mrs. Bradley's fanciful speculations as to the guilt of her father." Martyn is buoyed by the naming of another Butcher's Shop character, though! "Cleaver Wright. Nobody seems to mention how apt a name that might [be] for the Butcher of Rupert…"

J.F. Norris – "[Gladys Mitchell] threw an eleventh hour twist into the works, a twist that seems a nod to her colleague Agatha Christie who loved that sort of reveal... [I can't quote more without giving away the murderer's identity! – JH] Overall, this book is a fun entry in the series but I prefer her later books (the late '40s through the mid '60s) in which the plots are less full of hi-jinks and Wodehousian nonsense and are more contained and cohesive."

Catherine Dilts – "The Mystery of a Butcher’s Shop is a fun read, with zany action scenes, distinct characters, and an ending that surprised me not because of whodunit, but because of Mrs. Bradley’s philosophical reaction to the conclusion of her investigation. In the end, I like Mrs. Bradley. Who couldn’t like a woman who is 'bored to death by mere limbs and joints'?"

And Nick Fuller, whose site The Grandest Game in the World is a treasure trove of contemporarily-published GAD mystery fiction reviews, shares these notes:

"Several newspapers praised the book's humour. Outlook's W.R. Brooks called it 'irresistibly amusing, and a good detective story of the English country house school'. In the States, Will Cuppy said 'Miss Mitchell has done a neat job, suitable for persons who can do with some farcical proceedings while they are pondering upon the dismembered corpse', and the Springfield Republican noted that 'the story is written in a light vein, and the author pokes fun impartially at all her characters'."

Until then, happy reading! (And visit this site for more GAD and contemporary mystery reviews – books by Michael Innes, Gregory McDonald, Ross MacDonald, and Nicholas Blake should be represented soon.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed