It is no surprise that I live and read for just that discovery. My first true literary love, the wonderfully imaginative Mrs Bradley series by the wonderfully prolific GAD novelist Gladys Mitchell, bloomed when I found a paperback copy of 1945’s The Rising of the Moon in a remainder bin. I was so taken with this author’s prose and plotting – the former at times perhaps more sturdy than the latter – that I launched a tribute website to introduce more readers to her books.

And each time I discover a “new” writer of crime fiction and delight in his or her storytelling strengths, I celebrate and know that I’m likely in for the long haul: examples include Nicolas Freeling’s series featuring Dutch detective Pieter Van der Valk; the Lew Archer tales of Ross MacDonald; and most recently, the dark and quirky Harpur & Iles stories by Bill James. These writers are far from unknown, but the initial read of one of their books felt serendipitous as I fell under their narrative spells.

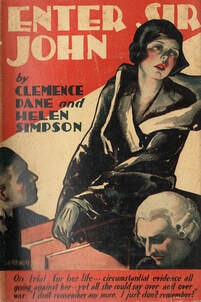

A friendly, philosophical correspondent named Pavel recently reminded me of the works of Helen Simpson as he described how much he enjoyed this author’s prose. As far as I know, my exposure to Helen Simpson and her work was limited to her chapter contribution in the round-robin detective novel Ask a Policeman (1933). In that book penned by members of The Detection Club, Simpson swaps detectives (one of the book’s concepts) with Gladys Mitchell and inserts Adela into the moniker of Beatrice Lestrange Bradley, an addition which delighted Mitchell. The timing seemed right and, thanks to Pavel, my interest was piqued, so I ordered Simpson’s first mystery novel, co-written with Clemence Dane, through academic interlibrary loan and let Sir John Saumarez take the stage.

The plot of Enter Sir John is simple and engaging: Martella Baring stands accused of murdering fellow actress Magda Druce after an ill-tempered and ill-fated evening visit to the victim’s home. Standing in the dock, Martella comes off as beautiful and cool as she dispassionately surveys her surroundings and awaits her fate. But stage actor and producer Sir John Saumarez is in attendance, and the actress’s performance stays with him after the jury brings in a verdict of Guilty.

As a working acquaintance of Gordon Druce, the dead woman’s husband, Sir John learns more about the events of the fateful night. He is troubled by a bit of set dressing, namely an empty wine glass that should either have been full or not there at all. Using his connections and his charm, Sir John begins an amateur investigation that leads him to a new suspect, and one who will give the professional actor a very robust run-around before the case can be resolved and Martella Baring can be exonerated.

The book’s authors were both familiar with the world of the theatre and the sometimes vivid personalities of those who choose to perform on stage. Being playwrights in addition to prose writers, Clemence Dane and Helen Simpson bring their penchants for character creation and dramatic plotting to their story of a woman wrongfully accused of murder. Indeed, I think it is the authors’ ability to set scenes and bring to life a number of Enter Sir John’s incidental characters that makes the tale so entertaining.

From its opening-pages nod to the porter of Macbeth – each chapter begins with a quoted line from a Shakespeare play – we learn less about the principals, i.e., Sir John Saumarez and the actress he is trying to save from the gallows, and more about the scrappy, lived-in demeanors of those cast in supporting roles. It is a winning strategy: characters like Novello and Doucie Markham, perpetually behind in their rent but hoping that Sir John’s interest in the case can be parlayed into employment within his theatrical company, are spirited, sympathetic, and very amusing. And while not integral to the plot, a chapter recording the debate around the jury table is beautifully observed and quite comical, with several figures adroitly sketched to highlight their quirks and qualities.

The other element that might be bothersome to 21st century readers concerns the killer’s motive for disposing of Magda Druce, as well as that character’s… well, character. The problem is that both aspects are outdated, to put it kindly, although I can appreciate the societal pressures this rather pathetic murderer might have felt (or paranoically imagined) while living and looking for work in 1920s London. The book loses its pace around the two-thirds mark, when the culprit is revealed and must be searched for, only to be found and then lost again, not once but twice. It’s a curious, prolonged dénouement to an otherwise enjoyable book.

As an authorial pair, Dane and Simpson wrote two more detective stories on the heels of Enter Sir John. I hope to read and review these soon, as their debut crime fiction production delivered a worthwhile performance, even with some third-act stumbles.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed