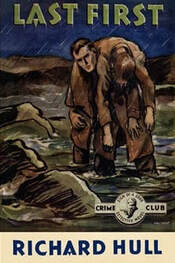

So states the dedication of 1947's Last First, perhaps the author's boldest experiment in narrative order, where one reads the last chapter first and then spends the rest of the book watching the story build to that moment. It is a gimmick, all right, especially as the mystery genre is often all about the final chapter, with its revelations of who, how, and why crimes have been committed. To provide this information at the very top is innovative, to say the least, with many traps attendant.

But that's not what Richard Hull has actually attempted here.

One of accountant-turned-writer Richard Hull's genre strengths is his continued interest in trying new storytelling approaches and set-ups: his celebrated debut novel, 1934's The Murder of My Aunt, is an inverted tale where the hopeful murderer documents his attempts in diary form (which we are reading); the flawed but amusing The Murderers of Monty (1937) hinges on violence drafted and agreed to by a limited partnership committee; and the highly enjoyable My Own Murderer (1940) has us rooting for an amoral lawyer who tries to frame his criminal client. Hull's output is inconsistent, but nearly all his stories show some curiosity about how expectations of the detective fiction format can be subverted and challenged.

So it is with Last First, a book that I found not wholly successful but intriguing in parts. How does the author manage that tricky "last chapter first" gimmick? If all is truly revealed from the beginning, i.e., if the identity of the murderer, the explanation of the crime, and the fate of the guilty party are all announced before the story even starts, then there is no suspense and little reason to read the detective story, as the reader can no longer play the game. To avoid this, Hull paints a climax where the characters are not positively identified. A man is atop a bluff, holding a gun, while three figures below walk across the rocks and grasses that trace the winding waters of Ben Deren. Rosemary Mordaunt, the only person not referred to by a nickname – everyone else is "Bongo" or "Greggy" or "Hoots", a childish naming habit of the flirtatious secretary – joins the man with a gun. Soon, the gun is fired, but is it to "warn off" a man below from stepping away from the path and into a dangerous bog or for a more sinister reason?

So we have a rather disorienting final scene first, followed by the story told chronologically to get the characters to this moment. The striking Scottish setting is agreeable and I was willing to let the story unwind – or more precisely meander – in order to complete the circle. The drama that unfolds at Portray Hotel and environs, however, is not especially believable or engaging, unfortunately. As I have felt with some other Hull novels, such as A Matter of Nerves and Invitation to an Inquest (both 1950), some of the scenes in Last First have a sort of page-filling, time-marking quality, and they are scenes that prove mostly unnecessary to the greater plot and are built upon chattery dialogue that doesn’t offer much in the way of clues or even characterization. I notice that Hull's last six books, including this one, have a tendency to wrap up at exactly 192 pages; it makes me wonder if he was writing to a strict word count, which in turn makes me suspect that those desultory conversations that pad the middle of these stories help to serve that purpose.

Still, Last First has moments of interest, although I have to wonder what a truly brilliant mystery fiction plotter might have done with the challenge of telling a detective story with the last chapter presented as the start of the narrative. (Note that the challenge would lie in tackling a true fair-play whodunit this way; a thriller tale where climax is offered up first seems a lot easier to craft, and in fact that's partly what Hull leans on here.) One wonders what Agatha Christie or Nicholas Blake might have done with the conceit. As for Richard Hull, he makes an attractive fly-cast, but falls short of hooking a fish of any substance this time around.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed