While Blake shapes and complicates his plot with his customary inventiveness and attention to detail, there is something that keeps me at a distance from the characters and, ultimately, from the thrill of the chase itself. Snowman's middle section, with its theories and interviews and evidence gathering, is technically successful, but I found it difficult to focus on and engage with it all. The group of suspects should be engaging, and each character has enough definition to fill his or her assigned role in the larger drama. All the same, there's an overriding feeling of chess-play at work, with figures moved around on the board (or biding their time on their square) simply for the game's sake, so it is difficult at times to feel invested in the story of people touched by tragedy.

This criticism may have its roots in Blake's handling of Elizabeth Restorick, the victim at the center of the story. The reader never really becomes acquainted with her as a personality, yet she makes an unforgettable introduction as a corpse, hanging from a beam, her body naked and her face painted. Then we learn (through Nigel) of her troubled adolescence and adult addictions, and she becomes the impetus for future murderous acts. All this should inspire an exemplary drama on the page that has the fatalistic propulsion of Macbeth, but the mystery stays academic and somewhat abstract. I'm also setting the standard high simply because Blake, the pen name for poet Cecil Day-Lewis, has delivered several excellent crime stories with strong characterization and engrossing puzzle plotting, including Thou Shell of Death (1936) and The Beast Must Die (1938).

By the time Strangeways arrives at the climax leading to his extraordinary solution, however, all torpor has been shaken off. And the author's tying up of all of his threads -- with more than a little hypothesizing about motives and mechanics of the characters by his detective -- lands another rather extreme effect: it is an innovative and bold solution that pushes the bounds of accepted reality for the reader.

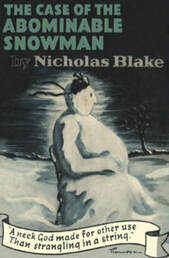

I say this because at least two elements require a faith (or suspension of disbelief) that a certain character would act almost counterintuitively to what a typical person would do under similar circumstances. To analyze either predicament here would require spoilers, and the enjoyable surprise in the revelations for new readers is too delicate to destroy. And in vaudeville, there is a delightful maxim/warning for its audience: "You buy the premise, you buy the bit." If you can believe two characters in this story would choose an extreme road of action over a far more practical pathway to see justice done, then The Case of the Abominable Snowman provides one of the most unusual and original resolutions in all of Golden Age Detection fiction.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed